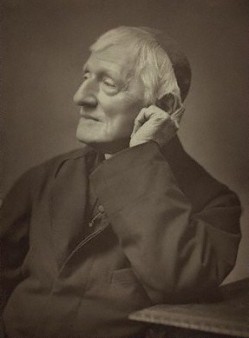

John Kezel, PhD,

The Campion Institute, Newman Conference on 23 October 2010, Fordham University, Lincoln Campus New York City

I cannot express adequately how pleased I am to be a part of this celebration of Blessed John Henry Newman’s beatification last month. I am especially pleased to be honoring Newman here at Fordham. Many of you are probably familiar with Newman’s statement about his conversion: “Catholics did not make us Catholics; Oxford made us Catholics.” Well, I can proclaim with equal boldness and pride: Fordham made me a Newmanist! Of course, as a born Catholic and the grandson of an Episcopalian convert to the Church, I had always heard of Newman and respected his memory. I learned various facts about him while a student of the Sisters of Mercy at St. John’s Grammar School in Stamford, Connecticut, and even more from the Jesuits at Fairfield Prep and Fairfield University. Indeed, I can remember a very snowy day back in the 1960’s when my class had been given jug for some misdemeanor and we all had to stand at attention balancing our notepads in our left hand while we wrote over and over again Newman’s classic “Definition of a Gentleman” until Father Alfred Morris was sure that it had made its effect on us. But it was only when I came to Fordham’s Graduate School and took a year-long class on Victorian Literature that – like so many of us here today – I fell in love with Newman: the man, the priest, the thinker, and the saint. I owe this blossoming devotion to all-things Newman to my professor, the late Vincent Ferrer Blehl of the Society of Jesus. Vinnie, a well-known Newman scholar and one of the editors of Newman’s letters, brought Newman alive to his students so that you felt you were reading the words of a contemporary friend rather than the works of a master of English prose. None of us was surprised when Vinnie Blehl became chairman of the Historical Committee set up to examine Newman’s life, virtues, and reputation for sanctity. This committee completed its findings in 1986 when Fr. Blehl became Postulator of the Cause for the Canonization of John Henry Newman. It was Vinnie Blehl who drew up the case for Newman’s holiness that was unanimously approved by the Committee of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, so that Pope John Paul II declared, in January 1991, that Newman was a fit candidate for canonization. Thus, I am very proud to stand here today as one of Fr. Vincent Ferrer Blehl’s students and friends.

Paraphrasing St. Paul (Phil 2:16), I think I am justified in saying that Cardinal Newman – in imitation of the κενωσις or the self-emptying of the humble Christ – did not think of sanctity as a αρπαγμον, something to be grasped at; like St. Philip Neri, the founder of the Oratory, Newman did not want people considering him a saint. To one correspondent, he wrote, “I have no tendency to be a saint – it is a sad thing to say so.” Newman went on to contend that “Saints are not literary men; they do not love the classics, they do not write Tales.” It is almost as if Newman believed that, as the author of two novels – albeit religious ones, he could not be a saint. Well, I for one am glad that – Pope Benedict XVI does not agree with this view of religious writers. Consequently, I have decided today to speak about Newman’s influence on another Catholic writer, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, one of the most popular authors in modern English literature. I have to confess that I was somewhat late coming to Tolkien. The first time I heard about Tolkien was in my junior year of college. Waiting for a Greek class on Euripides to begin, one of my friends began talking about the cult surrounding The Lord of the Rings. I determined then and there that I would never become a Frodo Freak or a Gandolf Ghouley. Once again, Fordham changed my mind. Two of my Anglo-Saxon mentors – Charlie Donahue and Father Edwin Cuffe – both told me of their admiration for this Oxford scholar. So I relented and have never looked back.

When I first read Tolkien, what most impressed me was the manner in which Tolkien used his knowledge of Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse culture and literature to mold his own mythology for England – for example, the way that he uses the dragon episode in Beowulf as a major source in The Hobbit or the way he borrows the names of some of his dwarfs – or, as Tolkien would prefer, dwarves – from Old Norse literature. Gradually I began to become more interested in the religious themes that flow through Tolkien’s work, especially The Lord of the Rings. Eventually, as I became familiar with Tolkien’s biography, I began to appreciate the importance of Cardinal Newman as a major source for his writings – despite the fact that Tolkien never openly acknowledges him.

To begin to understand this influence, we need to review some important facts in Tolkien’s life. In 1892, two years after Newman’s death, Tolkien was born to British parents in Bloemfontein, South Africa, where he was baptized John Ronald Reuel in the Anglican Cathedral. When he was three, Tolkien’s parents decided to return to Great Britain. His mother Mabel sailed to England with Tolkien and his younger brother Hilary. Unfortunately, her husband Arthur contracted rheumatic fever and died before he could leave South Africa. Because of her lack of money, Mabel moved into a small house in Sarehole, a rural suburb of Birmingham. Unable to afford schooling, Mabel taught her two sons at home giving them lessons in Latin, French, German, art and music. Unfortunately, her conversion to Catholicism in 1900 alienated both her own family and her husband’s. She further enraged them by bringing up her sons in the Catholic faith. In order that John could attend his father’s alma mater, King Edward’s School, Mabel moved into Birmingham itself where she attended church at Cardinal Newman’s Oratory. On the 14th of November in 1904 Mabel died of diabetes. Fearing that their relatives would not allow John and Hilary to remain Catholic, she appointed, in her will, the Oratorian Fr. Frances Xavier Morgan as their guardian. Fr. Morgan used his own money to raise the two boys whom he housed close to the Oratory. Each morning, the two brothers served Fr. Morgan’s mass before eating breakfast in the Oratorian refectory. Tolkien described himself as “virtually a junior inmate of the Oratory house.” It was Fr. Morgan, a friend of Newman’s, who must have first introduced the life and writings of the great Cardinal to Tolkien. Tolkien followed the example of Newman and went to Oxford where eventually he became Professor of Anglo-Saxon. A married man with children, Tolkien remained a devout Catholic all his life and revered his mother whom he truly considered a martyr for her Catholic faith. Tolkien lived to see his trilogy become a cult classic. He died on the 2nd of September 1973.

Just from this short biography, one can see important similarities: both Newman and Tolkien were English converts to Catholicism who became important figures at Oxford University and are today remembered as great men of letters. In this talk, I would like to illustrate my suggestion that Cardinal Newman was a principal source for Tolkien’s trilogy. It is certainly true that both men have interested their readers by investigating the world of spiritual realities that supports the world as we know it. In his well-known autobiography, the Apologia Pro Vita Sua, Newman reveals that his interest in the reality of a spiritual world began in his early childhood with the reading of the Bible as well as with fantasy literature such as The Arabian Nights, whose magical tales he wished were true. Likewise, the young Tolkien delighted in Alice in Wonderland and the imaginative fairytales of George Macdonald. As they grew up, both men saw this early interest in spiritual worlds as a blessing, for it brought home to them an important truth. As Newman writes, “we are then in a world of spirits, as well as in a world of sense, and we hold communion with it, and take part in it, though we are not conscious of doing so.”

In The Lord of the Rings, when the men of Rohan learn that hobbits really do exist, one of them asks, “Do we walk in legends or on the green earth in the daylight?” Aragorn replies that we can live in both worlds and furthermore, we should not take such things as the “green earth” for granted because it too “is a mighty matter of legend” though we “tread it under the light of day!” Over and over again in their writings both Newman and Tolkien remind us of this truth. Moreover, they make it clear that we should reach out in fellowship to the inhabitants of other worlds: be they saints, angels, elves, or hobbits.

In a sermon entitled “The Invisible World,” Newman states that we should not consider the spiritual world strange or remote because we encounter and communicate daily with a “third world” – the world of animals. It is clear that these creatures have passions, habits, and even a certain accountableness; but what do we really know about them? (I think it’s evident that Newman knew some cats!) While it may seem strange for Newman to bring up our fellowship with the animal kingdom, it would seem that such fellowship is part of the spirituality of the Oratorians.

St. Philip Neri, who founded the Oratory in the sixteenth century at around the same time that St. Ignatius founded the Jesuits, was fond of keeping animals in the religious house. Animals seemed to reciprocate his affection. Once, his friend St. Charles Borromeo brought his dog Capriccio with him on a visit to St. Philip. Capriccio refused to go home and from then on paid no attention to anyone but Philip. This lovable saint was not always so successful in his dealings with so-called pets. He had a favorite cat that refused to move with St. Philip when he changed residences in Rome, the cat preferring to stay in its old haunts. Philip, however, never stopped caring for this rather ungrateful feline. Every evening, he would send some of his young followers back to his old home to feed Kitty and report back on its health and appetite. Just because you no longer live together does not mean that the duties of fellowship have ended.

Newman followed his founder’s example by befriending an old pony that had been given to him by a friend. Newman established a home for this pony named Charlie at the Oratorians’ country villa in Rednal. Newman delighted in recounting the antics of his pet and fourteen years later cared for Charlie when he was dying – burying him under two sycamore trees that he hoped would be a living monument to his “virtuous” pony. No doubt, Fr. Morgan used to point out this spot to Tolkien and his brother who often used to visit Rednal.

I do not think I am wrong in seeing allusions to Charlie in Sam’s beloved old pony Bill or in Gandalf’s relationship with Shadowfax, the king of Rohan’s own horse, who like St. Philip’s Capriccio left his owner and would only attend to Gandalf. The wizard returns this affection and, when they are in the city of Gondor, sends off Pippin to see how well he has been housed – shades of St. Philip’s cat!

Fellowship in both Newman and Tolkien extends to the world itself. In a sermon called “God’s Will the End of Life,” Newman tells his audience to look at the modern industrialized city if they want to see how out of joint we are with the Creator. What do we find? Overly crowded streets, the constant din of traffic, factories, slums, and overhead “a canopy of smoke” shrouding “God’s day from the realms of obstinate sullen toil.” How similar is this description to those of Tolkien when he describes the dehumanizing destruction of nature in Moria, Mordor, Isengard, and eventually even in the Shire. As the Hobbit Sam puts it, there’s devilry at work!

I think it is important to point out, that neither Tolkien nor Newman is attacking modern scientific developments or the increasing globalization of society or even democratic principles. What they are attacking is a society that worships mindless progress and industrialization: namely economic growth that excludes those human qualities that make a society more than just a collection of individuals, each pursuing his or her own end. What both Newman and Tolkien hold up as the ideal is a society that operates for the fulfillment of each of its members, who together form a community in fellowship with all of Creation and in fellowship with God – in other words, a society based on the principles of Christian Humanism.

If we want to explore further what Tolkien was attempting to do with this theme of Christian fellowship and the role of Newman’s influence, we have to return to Tolkien’s biography. Anyone who has studied his life knows that Tolkien was the sort of man that Dr. Samuel Johnson called “clubbable”; he enjoyed intelligent, like-minded men whose company and conversation mutually inspire each other to live up to their ideals and accomplish great things. One immediately thinks of the Inklings, that Oxford group of friends that included Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Charles Williams. Well, long before the Inklings, the youthful Tolkien belonged to a group known as the TCBS, initials that stand for Tea Club, Barrovian Society. This club, composed of students from King Edward’s School, the exclusive public school that Tolkien attended, used to meet in the Tea Room of Barrows Store in Birmingham. Eventually the club centered on four major members, each of whom brought a specialization: Christopher Wiseman, the expert on music and natural sciences; R.Q. Gilson, called Rob, a lover of Renaissance painting and the eighteenth century; Geoffrey Bache Smith, known as GBS, knowledgeable about English literature, especially poetry; and finally Tolkien, called John Ronald, versed in Germanic languages and philology. Tolkien was the only Catholic in the group, but all four young men hoped to contribute to a moral and cultural renewal in England – as G.B. Smith put it, “to drive from life, letters, the stage and society that dabbling in and hankering after the unpleasant sides and incidents in life and nature which have captured the larger and worse tastes in Oxford, London and the world….to reestablish sanity, cleanliness, and the love of real and true beauty in everybody’s breast.” After they graduated, Wiseman and Gilson went off to Cambridge while Tolkien and Smith went to Oxford. Nevertheless, the four friends kept in contact and ultimately set up an important meeting of the TCBS at Wiseman’s London home on December 12th and 13th, 1914. During this weekend, they spoke about their future artistic goals. This meeting, afterwards known as the Council of London, was very significant for Tolkien, who claimed that he found there “a voice for all kinds of pent up things and a tremendous opening up of everything for me.” At the Council of London, Tolkien determined that his future involved poetry and writing an epic.

What is important to keep in mind here is how early in Tolkien’s life appeared his motive and his desire to write an epic, a mythology for England, especially when we recall that the first volume of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring was not published until August 1954, forty years after the four members of the TCBS met for the Council of London. In 1951, Tolkien wrote to Milton Waldman, a Catholic member of the Collins publishing firm, about his long-standing desire to write a myth for England:

I was from early days grieved by the poverty of my own beloved country: it had

no stories of its own (bound up with its tongue and soil), not of the quality that

I sought, and found…in legends of other lands….nothing English, save

impoverished chap-book stuff….

Once upon a time…I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected

legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-

story…which I could dedicate simply to: to England; to my country. It should

possess the tone and quality that I desire, somewhat cool and clear, be redolent

of our ‘air’ (the lime and soil of the North West, meaning Britain and the

hither parts of Europe…it should be ‘high’, purged of the gross, and fit for the

more adult mind of a land long now steeped in poetry.

It is interesting to note that Tolkien told the American scholar Clyde S. Kilby, who was helping him put together The Silmarillion, the background mythology of LOTR, that he had even considered dedicating this final work to Queen Elizabeth II, so seriously did he consider the importance of what he was doing.

In actuality, Tolkien began to write his mythology on September 24, 1914, with a poem entitled “The voyage of Earendel the Evening Star” that begins with the following lines:

Earendel sprang up from the Ocean’s cup

In the Gloom of the mid-world’s rim;

From the door of Night as a ray of light

Leapt over the twilight brim,

And launching his bark like a silver spark

From the golden-fading sand

Down the sunlit breath of Day’s fiery death

He sped from Westerland.

Tolkien seems to have received inspiration for his landscape descriptions from a walking holiday that he had taken the previous month with Father Vincent Reade, a priest of Newman’s Birmingham Oratory. For two weeks Tolkien and Fr. Reade explored the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall where “the sun beats down…and a huge Atlantic swell smashes and spouts over the snags and reefs” in a “weird” and “eerie” country setting.

There may be an even more significant connection to Newman in this first attempt at myth-making. Tolkien was inspired to write “The Voyage of Earendel” when he was reading the Anglo-Saxon poem Crist, the Christ, by the eighth-century poet Cynewulf, and came upon the following two lines:

Eala Earendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended.

I would translate them as “Lo the dayspring, brightest of angels, sent to men over middlearth.” Tolkien was struck by the beauty of the word for “dayspring” – Earendel – and used it as the personal name of the star Venus. Now, you may be wondering what this has got to do with Blessed John Henry. The section of Cynewulf’s Crist that these lines come from is a poetic meditation on the famous O-Antiphons of Advent, the seven antiphons for the Magnificat sung from the 17th of December until the 23rd. The lines Tolkien loved no doubt go with the antiphon for the 21st: O Oriens, Splendor lucis aeternae, et sol justitae: Veni et illumina sedentes in tenebris et umbra mortis: (O Dayspring, splendor of the eternal light and sun of justice: Come and shine on those sitting in darkness and the shadow of death). Cardinal Newman was very fond of the seven O-Antiphons and suggested using them when making “A Short Visit to the Blessed Sacrament before Meditation.” I cannot but wonder whether Tolkien himself, fond of visiting the Blessed Sacrament, was accustomed to reciting this particular antiphon which Newman ascribed to Thursday. It certainly reminds one of the imagery not only of Newman’s “Lead, Kindly Light” but of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings whose major theme is mankind fighting against the powers of darkness. What I can say for certain is that Tolkien had encountered Cynewulf’s language, of which he wrote “I felt a curious thrill as if something has stirred in me, half wakened from sleep. There was something very remote and strange and beautiful behind those words, if I could grasp it, far beyond ancient English.” Some time in the autumn or early winter of 1914, Tolkien showed his completed poem on the “Voyage of Earendel” to G.B. Smith of the TCBS and admits to Smith that he does not yet know what the poem is really about but promises that he will “try to find out.” I wonder if Tolkien realized that his quest for this knowledge would consume the rest of his life.

Just at the time that Tolkien and his three friends were dedicating their lives to reforming the corrupt state of arts and attitudes in England, they are confronted with the reality of World War I. When Tolkien and Father Reade were exploring Cornwall, Britain declared war on Germany. Christopher Wiseman joined the navy, while Rob Gilson, G.B. Smith, and Tolkien joined the army and were sent to France. On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, Rob Gilson was killed. G.B. Smith wrote to Tolkien: “Now one realizes in despair what the TCBS really was. O my dear John Ronald what ever are we going to do?” In his reply to Smith, Tolkien referred to the hopes of the four friends that the TCBS would be

A great instrument in God’s hands – a mover, a doer, even an achiever of

great things, a beginner at the very least of large things….

What I meant…was that the TCBS had been granted some spark of

fire – certainly as a body if not singly – that was destined to kindle a new

light, or what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world; that the

TCBS was destined to testify for God and Truth in a more direct way even

than by laying down its several lives in this war.

Tolkien went back to fighting in the trenches where he was most impressed, not by his fellow officers, but by the ordinary British soldiers who remained loyal and decent – despite what Tolkien called the “animal horror” of trench warfare. In late October 1916 Tolkien himself came down with trench fever, an illness carried by lice; eventually in November he was sent back to England to recover. The following month, G.B. Smith was killed by a shell blast. Shortly before, he wrote to Tolkien:

My chief consolation is that if I am scuppered tonight…there will still be left a

member of the great TCBS to voice what I dreamed and what we all agreed

upon….May God bless you, my dear John Ronald, and may you say the things

I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them….

By the war’s end, only Tolkien and Christopher Wiseman remained alive. Wiseman wrote to his friend, “You ought to start the epic”; but for the most part, he does not play a significant role in Tolkien’s literary career. Ironically, his sister Margaret does; she became a Catholic and a Benedictine num, Mother Mary St. John, at Oulton Abbey from where she encouraged him with her prayers.

For me, Newman’s influence on Tolkien involves far more than isolated images and concepts. I believe that Tolkien centers his entire work on fundamental ideas found in Newman’s writing. On one level, I view The Lord of the Rings as a Bildungsroman, a novel that deals with the education of its principal characters The more I read Tolkien the more I see Gandalf as a sort of fictionalized Newman. When Newman was at Oxford fighting to make the Church of England more Catholic and less Protestant, he was criticized as being a dangerous influence on the student body – leading them astray with the fireworks of his ideas, luring them to the “hocus pocus” of Catholicism more like a magician than a minister. Gandalf the wizard fits in nicely with this caricature of Newman. When Gandalf first appears after coming back from the dead, he is wearing a “wide-brimmed hat!” Could this possibly be an allusion to the wide-brimmed red hat Newman receives as a cardinal and that vindicates his years of being under a cloud? Gandalf even looks like the mature Newman who often complained that the anxieties and frustrations he had endured left his face so lined that he looked sad even when he was happy. Note what the hobbit Pippin says about Gandalf’s appearance:

Pippin glanced in some wonder at the face now close beside his own, for the sound

of that laugh had been gay and merry. Yet in the wizard’s face he saw at first only

lines of care and sorrow; though as he looked more intently he perceived that under

all there was a great joy: a fountain of mirth enough to set a kingdom laughing, were

it to gush forth.

For those who cannot see Newman as a fountain of mirth, they should recall visitors to this “great man of letters” who found him “full of fun.” They should also recall that his grandnephew P.G. Wodehouse is one of the greatest humorists in English – the acorn does not fall far from the tree. As a young man, Newman was once forced to take on a paying student to make ninety pounds in the summer. He was a particularly obnoxious student; Newman called him “a little wretch.” When he had finally completed this dreadful task, he wrote to his sister Harriet that he was at last free: “Liber sum – and I have been humming, whistling, and laughing out loud to myself all day. I can hardly keep from jumping about.”

If we can view Gandalf as a Newman – type figure, then we can also see the four hobbits (Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin) as his students. These natives of the Shire are just the sort of students Newman liked. Throughout The Lord of the Rings, we are repeatedly reminded that they are courteous to a fault and peace-loving. Never has a hobbit within the Shire killed another hobbit. That’s one of the reasons, Frodo and Sam are horrified to think that the violent, inhospitable Gollum is actually a hobbit (though not of the Shire, thank goodness!). Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin are naturally disposed to become the sort of gentlemen that Newman considered the hallmark of a university education. I’m sure most of you at one time or another have read Newman’s classic definition of a gentleman, summed up as “one who never inflicts pain.”

I always think of Merry and Pippin as true representatives of the Oxbridge tradition – what with their drawling slang and their fondness for pipes. By the end of the trilogy, they have matured into proper young aristocrats who have literally grown in stature. Sam and Frodo, on the other hand, have become the noblest of gentlemen. The Jesuit poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins (received into the Catholic Church by Cardinal Newman), once wrote that the true gentleman was the one who most resembled Christ who did not lord it over others but emptied himself of his divinity and in humble obedience to the Father died for us on a cross. Who can read about the experiences Frodo and Sam undergo in “the land of Shadow” without thinking about the Stations of the Cross?

In his “university,” Gandalf follows Newman’s suggestions about teaching and learning, all of which center on fellowship, a loving relationship between faculty and their pupils, as well as a warm collegiality among the students themselves. Gandalf also follows Newman in preferring a tutorial system over mere lecturing. Gandalf is quite capable of giving good lectures as we see at the Council of Elrond in Rivendell (itself a fantasy version of Oxford with its towers, bells, gardens, rivers and study halls). Nevertheless, Gandalf seems far more at home when he can sit back in a comfy chair, light his pipe, and engage in friendly banter with his pupil on those things that really matter. Like a good tutor, Gandalf knows when to withdraw and let pupils learn on their own. He also seems to be a great believer in study abroad and bringing in an occasional guest lecturer: the Lady Galadriel for ethics, Aragorn for political science, and the ancient Fangorn for world history. At other times, he leaves his pupils to themselves, for as Newman pointed out, the students in their conversations and debates are often their own best teachers. In all of his pedagogical techniques, Gandalf’s aim remains that of Newman: the promotion of “intellectual culture” – which Newman defines as educating “the intellect to reason well in all matters, to reach out towards truth, and to grasp it”: the ability to see things as they are.

When Newman became a cardinal, he took as his motto: cor ad cor loquitur [heart speaks to heart]. As we have seen, this could also be Gandalf’s motto as he lovingly prepares the hobbits to confront the evil of their day: the excessive, cold rationalism of Saruman and Sauron’s lust of power. In much the same way, Newman too was preparing his followers to oppose the skepticism and alienating force of a nineteenth century liberalism that would deny the truth of revelation and unsettle the mind of believers. Thus we have both Gandalf and Newman urging on their followers, encouraging them to stand united against a foe that can ultimately only be identified as the enemy of mankind. As Gandalf explains to the Steward of Gondor:

But I will say this: the rule of no realm is mine, neither of Gondor nor any other, great or small. But all worthy things that are in peril as the world now stands, those are my care. And for my part, I shall not wholly fail of my task, though Gondor perish, if anything passes through this night that can still grow fair or bear fruit and flower in days to come. For I also am a steward.

In confronting such evils – surely a great cause of gloom and doom – both Newman and Gandalf teach their followers to remain cheerful, not allowing themselves to be overwhelmed by the immensity of these problems. In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf and his fellows view their obstacles in the light of the Anglo-Saxon genre of “riddles.” It is significant that, in Newman’s time and afterward, the priests at the Birmingham Oratory would – after dinner – extemporaneously discuss a problem or complex situation that was identified as a “riddle.” Gandalf’s use of riddles in his school allows his students to view their problems almost as games that unite the participants in joyful fellowship as they focus their energies on winning.

It is also significant that, in their educational programs, both Newman and Gandalf believe that learning traditional literature that has withstood the test of time remains the best preparation for dealing with present problems: whereas Newman proposes the classical literature of Greece and Rome, Gandalf uses the tales and songs that have been treasured throughout the ages. Through applying the matter of these tales and songs to their present condition, each of the members of the fellowship sees that these are more than nursery rhymes or old wives’ tales. Ultimately, the whole fellowship comes to see that this literary heritage provides them with those truths needed to understand their present conditions and to overcome the almost insurmountable obstacles that confront them.

Viewing The Lord of the Rings as a work that celebrates Newman’s educational ideals will help us to appreciate what Tolkien was doing in this long labor of love. He clearly stated that the work was “hobbito-centric” that the four hobbits of the Shire were, for Tolkien, the most important protagonists in the novel. I don’t think that I am wrong if I see in these four loyal, high-minded, courageous friends a fictionalized portrait of the four idealistic friends of the TCBS. Merry, Pippin, Sam, and Frodo actually accomplish what Tolkien told G.B. Smith was their destiny: “to kindle a new light, or what is the same thing, rekindle an old light in the world.”

On December 25, 1840, John Henry Newman delivered a sermon at the height of the Oxford Movement when he was discovering the truth of Catholicism. He entitled this sermon “The Three Offices of Christ” and discussed the “three chief views which are vouchsafed to us of His Mediatorial office….Christ was Prophet, Priest, and King.” Newman explains these three offices or views:

Christ exercised His prophetical office in teaching, and in foretelling the

future; – in His sermon on the Mount, in His parables, in His prophecy of

the destruction of Jerusalem. He performed the priest’s service when He

died on the Cross, as a sacrifice; and when He consecrated the bread and

the cup to be a feast upon that sacrifice; and now that He intercedes for us

at the right hand of God. And He showed Himself as a conqueror, and a

king, in rising from the dead, in ascending into heaven, in sending down

the Spirit of grace, in converting the nations, and in forming His Church

to receive and to rule them.

As Newman demonstrates, Christ came into the world “to make a new world….to regenerate it in himself, to make a new beginning, to be the beginning of the creation of God, to gather together in one, and recapitulate all things in Himself.” Newman further maintains that when Christ ascended to the Father, he left His Church to carry out His three offices: not just by the hierarchy and the ministerial priesthood but by all Christians who, by virtue of their baptism, are called upon to actualize these three Christological offices in living out their own lives. As Newman concludes:

This is the glory of the Church, to speak, to do, and to suffer, with that grace

which Christ brought and diffused abroad. And it has run down even to the

skirts of her clothing. Not the few and the conspicuous alone, but all her

Children, high and low, who walk worthy of her and her Divine Lord, will be

shadows of Him. All of us are bound, according to our opportunities – first to

learn the truth; and moreover, we must not only know, but we must impart our

knowledge. Nor only so, but next we must bear witness to the truth. We must

not be afraid of the frowns or anger of the world, or mind its ridicule. If so be,

we must be willing to suffer for the truth. This was the new thing that Christ

brought into the world, a heavenly doctrine, a system of holy and supernatural

truths, which are to be received and transmitted, for He is our Prophet,

maintained even unto suffering after His pattern, who is our Priest, and obeyed,

for He is our king.

I think we have come to the heart of what Tolkien meant when he wrote that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work.” In Tolkien’s newly minted “Mythology for England,” he has created a brilliant image of the living Church at work in the world: Gandolf the Prophet, Aragorn the King, and Frodo the Priest who mediates the redemption of Middle Earth. Ultimately, the lesson that the four hobbits have learned is the lesson of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.

Thank you.