Westminster Cathedral, 2nd May 2009

Westminster Cathedral, 2nd May 2009

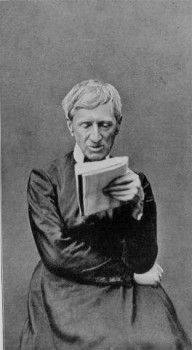

It is fitting to recall and to give thanks for past benefits of which we are the beneficiaries down to the present day. That is particularly appropriate on the occasion of an anniversary of jubilee. Our celebration today has precisely this purpose: we commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the foundation of The Oratory School by John Henry Cardinal Newman.

A group of Catholic laymen requested him to found a boarding school to provide boys coming from the small English Catholic community of the time with an education similar to that given in the public Schools but which would have a Catholic ethos.

This great dream became a reality on Monday 2nd May 1869, a century and a half ago, to the day, at Edgbaston, Birmingham. Sir John Acton, who was at the Oratory ten days before the opening, wrote: “The school is beginning with great hopes indeed, but in a small way to start with” (Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, Vol. XIX, p. 116). Indeed on that first day there were only seven boys, all of them sons of English converts. The School has had its good times and its challenging periods. During the Second World War numbers shrank to 27. Now, however, it flourishes. It has over 400 pupils and is the only all-boys senior Catholic school in the United Kingdom.

The staff and pupils in most schools know little or nothing about the person who founded their school. Not so with the Oratory School: it looks proudly back to the eminent educationalist, churchmen, convert and Servant of God, the Venerable John Henry Cardinal Newman, as its founder. The spirit of that great man has guided the school policy since the beginning and has given it that special character and tenor which is The Oratory School. Forty years ago the renowned Fr. Stephen Dessain of the Oratory, wrote about it: “Newman’s Oratory School, while remaining small, proved a real success, and its example and competition raised the standard of the other Catholic schools” (John Henry Newman, London 1966, p. 110).

Newman meant the school to be, as it has always been, a centre of academic excellence. It was to provide an all-round education where young minds were challenged: not so much having information pumped into them as having the best in them brought out. Education had to form the whole person, not simply the intellect. It also had to form and train a pupil’s character.

Newman himself, in the early years, loved to teach the boys at the School and often took the monthly examinations in Latin Grammar and syntax. He edited some plays and comedies from Latin authors, adapted for the use of the boys. He emphasised the value of learning by heart at a young age. He fostered music as a wholesome distraction from too much study: “To my mind, music is an important part of education” (Letters and Diaries, Vol. XXII, p. 42). He was keen that the School would do well in sports, also, a tradition that is proudly maintained down to the present. But all the while he did not omit teaching and formation in the faith, and he personally gave catechetical instruction to the senior boys and preached for them on Sundays.

In other words, he put his heart and soul into the task of educating the boys in the School. He got the same personal satisfaction in it as he did from tutoring the undergraduates at University. Listen to what he once wrote at a time when he was under the pressure of preparing an instalment of his famous Apologia every Thursday: “We are as yet very fortunate in our boys – and, if I could believe it to be God’s will, would turn away my thoughts from ever writing any thing, and should see, in the superintendence of these boys, the nearest return to my Oxford life – for, to my surprise, I find that Oxford “men” and schoolboys are but varieties of one species, and I think I should get on with the one as I got on with the other” (Letters and Diaries, Vol. XXI, p. 51).

A year ago, our present Holy Father wrote a Letter to the faithful of the Diocese and City of Rome on the urgent task of educating young people. In it he echoes certain truths that would have struck a chord with Newman and were part of his own principles of education: “Every true teacher knows that if he is to educate he must give a part of himself, and that it is only in this way that he can help his pupils overcome selfishness and become in their turn capable of authentic love … An education would be most impoverished if it were limited to providing notions and information, and neglect the important question about the truth, especially that truth which can be a guide in life” (L’Osservatore Romano, English edition, No 6, 6th February 2008, p. 10).

Newman himself sacrificed the things he cherished most for the sake of truth. And today, 2nd May, is the Feast of another renowned defender of the true faith, namely, St. Athanasius. Newman revered him as a special doctor of that sacred truth denied by the heretic Arius, namely, the truth of the divinity of Christ, the Son of God. He described him as “the most modest as well as the most authoritative of teachers” (Select Treatises of St. Athanasius, Vol. II, pp. 56-57).

Athanasius was one of those “highly-endowed men” who “will rescue the world for centuries to come”, one who “receives and transmits the sacred flame … fully purposed to send it on as bright as it has reached him; and thus the self-same fire, once kindled on Moriah [where Abraham’s faith and obedience were tested], though seeming at intervals to fail; has at length reached us in safety, and will in like manner, as we trust, be carried forward even to the end” (University Sermons, p. 97).

The Venerable John Henry Newman, your founder, was also one of those renowned educationalists and defenders of the faith who received the sacred flame of truth and passed it on. It sill burns brightly until the present day. The young boys at the School are being trained to enter a world where truth is often ridiculed and faith is ignored. Newman was keenly aware of the dangers that face them in a world, today more than ever, “with its polluting, withering, debasing, deadening influence”, a world “which promises them true good, then cheats them, and then makes them believe that there is no truth any where, and that they were fools for thinking it” (Parochial and Plain Sermons, Vol. VI, pp. 317-318).

Therefore, Newman firmly believed that boys and young men are being prepared for the world, so that they can manage to live in it without being deceived by its ways, and to influence it by the convinced conduct of their lives. “Who can overcome the world?” we read in the First Letter of St. John, “Only the man who believes that Jesus is the Son of God” (I Jn. 5:5).

The Oratory School has stamped upon it the educational ideal of Newman himself. Much depends on the personal influence for good that is exercised upon the young. He laid down “as a guiding principle” which he believed “to be the truth”, namely, “that the young for the most part cannot be driven, but on the other hand, are open to persuasion and the influence of kindness and personal attachment; and that, in consequence, they are to be kept straight by indirect contrivances rather than by authoritative enactments and naked prohibitions” (My Campaign in Ireland, Aberdeen 1896, p. 115).

And that brings us back to what Pope Benedict XVI, in the Letter already referred to, declares to be “the most delicate point in the task of education: finding the right balance between freedom and discipline. If no standard of behaviour and rule of life is applied even in small daily matters, the character is not formed and the person will not be ready to face the trials that will come in the future” (L’Osservatore Romano, Ibid.)

I congratulate and encourage the teachers and staff of The Oratory School on their dedication to the education of the boys in the spirit of Newman. And I ask the boys to appreciate what they receive and to prepare well in their school years for the challenges of life that lie before them.

One of Newman’s books, Meditations and Devotions, which gives us a fine selection of the Cardinal’s devotional papers and allows us a precious glimpse at his soul, was dedicated by the editor, Fr. William Neville, to the boys of the Oratory School. It has even been suggested by one of the teachers at the School, in a fine article he wrote, that many of the papers and meditations in that book could have been written for use on Retreat days for the boys at the School (cf. Andrew Nash, Newman’s Idea of a School). Be that as it may, I wish to conclude these words with two brief extracts from the many beautiful pages of this book. As you prepare for your future path of life, boys, the Cardinal seems to suggest the following reflection: “God has created me to do Him some definite service; He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to another. I have my mission – I never may know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. Somehow I am necessary for His purposes, as necessary in my place as an Archangel in his – if, indeed, I fail, He can raise another, as He could make the stones children of Abraham. Yet I have a part in this great work; I am a link in a chain, a bond of connexion between persons. He has not created me for naught. I shall do good, I shall do His work; I shall be an angel of peace, a preacher of truth in my own place, while not intending it, if I do but keep His commandments and serve Him in my calling. (Part III, I, p. 301).

And secondly, to be perfect in your actions, at present and hereafter, you need only do well the normal things of life. Your founder’s voice echoes down the years and gives the following ever-relevant advice with a wisdom that is always fresh and attractive: “If you ask me what you are to do in order to be perfect, I say, first – Do not lie in bed beyond the due time of rising; give your first thoughts to God; make a good visit to the Blessed Sacrament; say the Angelus devoutly, eat and drink to God’s glory; say the Rosary well; be recollected; keep out bad thoughts; make your evening meditation well; examine yourself daily; go to bed in good time, and you are already perfect. (A Short Road to Perfection, p. 286).

May the Oratory School prosper for the next century and a half, keeping alive the spirit of Newman’s educational dream.