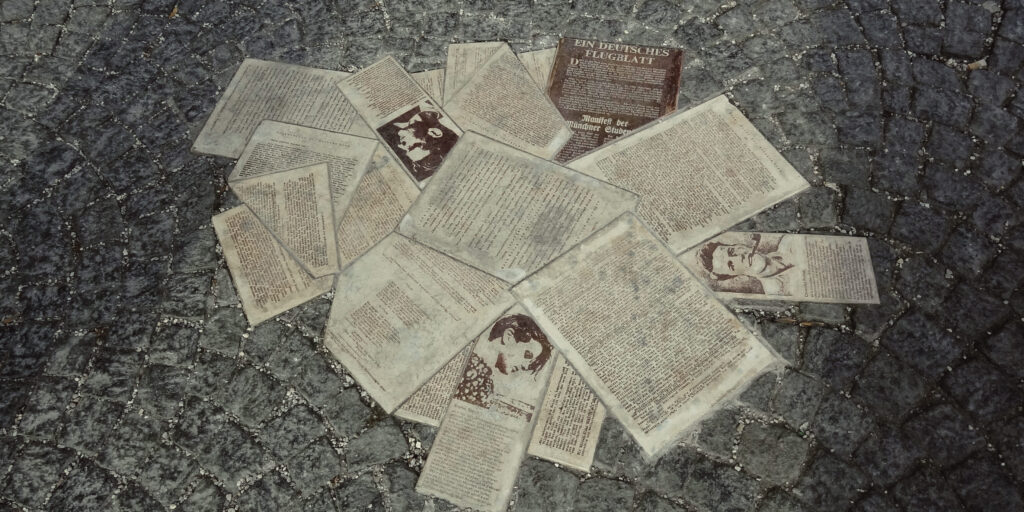

Eighty years ago, on February 18, 1943, Hans Scholl and his sister Sophie were caught distributing anti-Nazi leaflets in Munich University. Five days later they were tried and executed for high treason on Hitler’s direct orders. The Scholls belonged to a group of students who, using the nom de guerre of the White Rose, spoke out against National Socialism and circulated thousands of leaflets telling Germans of their moral duty to resist Hitler and his “atheistic war machine”. They also condemned the persecution of Jews in the year when Hitler began to implement the Final Solution – and were among the few to speak publicly of the Holocaust while it was taking place.

The Scholls and their friends are household names in Germany. Sophie has nearly 200 schools named after her; she was dubbed the greatest German woman of all time by a popular television series called Greatest Germans, and the film Sophie Scholl: the Final Days (2005) was nominated for an Oscar in the category Best Foreign Language Film.

After the conspirators of the failed July 20, 1944 attempt on Hitler’s life, the White Rose students are the best-known example of Germans who sought to resist the Nazis. That there were so few similar deeds shows just how difficult and dangerous resistance was, and how successful Nazi tactics had been in desensitising consciences and eliminating whatever stood in their way. Even the effort to maintain some form of inner or passive resistance required great determination.

Perhaps surprisingly, both Hans and Sophie were initially enthusiastic members of the Hitler Youth; they joined when membership was optional and against their father’s wishes, and even became group leaders. But they were disillusioned by their experiences, and began to oppose virulently every manifestation of Nazism. In search of meaning for their lives, they discovered in Christian writers, ancient and modern, answers to their deepest longings. From their letters and diaries we know that they were strongly influenced by St Augustine’s Confessions, Pascal’s Pensées and George Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest. Now it has become clear that their lives were also shaped by the writings of St John Henry Newman.

The man who brought Newman’s writings to the attention of the Munich students was the philosopher and cultural historian Theodor Haecker. Haecker had become a Catholic after translating Newman’s Grammar of Assent in 1921, and for the rest of his life Newman was his guiding star. He translated seven of Newman’s works, and on several occasions read excerpts from them at the illegal secret meetings Hans Scholl convened for his friends. Strange though it may seem, the insights of the Oxford academic were ideally suited to help these students make sense of the catastrophe they were living through.

Haecker’s influence is evident already in the first three White Rose leaflets, but his becomes the dominant voice in the fourth: this leaflet, written the day after Haecker had read the students some powerful Newman sermons, finishes with the words: “We will not be silent. We are your bad conscience. The White Rose will not leave you in peace! Please read and distribute!”

When Sophie’s boyfriend, a Luftwaffe officer called Fritz Hartnagel, was deployed to the Eastern Front in May 1942, Sophie’s parting gift was two volumes of Newman’s sermons. After witnessing the carnage in Russia, Fritz wrote to Sophie to say that reading Newman’s words in such an awful place was like tasting “drops of precious wine”.

In another letter, Fritz wrote: “We know by whom we were created, and that we stand in a relationship of moral obligation to our creator. Conscience gives us the capacity to distinguish between good and evil.” These words were taken almost verbatim from a sermon which Newman preached in Oxford called “The Testimony of Conscience”. In it, Newman explains that conscience is an echo of the voice of God enlightening each person to moral truth in specific situations. All of us, he argues, have a duty to obey a right conscience over and above all other considerations.

During the interrogation before her trial, Sophie said that it was her Christian conscience that had compelled her to oppose the Nazi regime non-violently. The same was true for Hans: he, like his sister, had found in Newman and other Christian writers the resources and inspiration to make sense of the brutal and demonic world around him.

Fritz Hartnagel was evacuated from Stalingrad just before the German army surrendered. In his last letter to Sophie, he laments the loss of the two volumes of Newman sermons she had given him – not knowing that Sophie was already dead when he was writing. When Fritz visited Sophie’s parents, he gave them a collection of Newman sermons translated by Theodor Haecker. Haecker himself also visited the Scholls, and signed the visitor’s book with Newman’s own motto, Cor ad Cor Loquitur (“Heart speaks to heart”).

Update 10 March 2023:

Traute Lafrenz-Page, the last survivor of the “White Rose” resistance group, died on 6 March 2023. She lived in the US state of South Carolina and was 103 years old. In 2019, she was awarded the Cross of Merit 1st Class of the Federal Republic of Germany. We gladly join the White Rose Foundation’s obituary:

“It is with sadness and great appreciation that the White Rose Foundation pays tribute to her courageous resistance and enduring witness. For decades Traute Lafrenz was a discreet and impressive witness of the White Rose.”

White Rose Foundation (own translation)

About the Autor

Paul Shrimpton

Paul Shrimpton has lived in Oxford since 1977, studying at Balliol College, then teaching at Magdalen College School. As an historian of education, he has been researching the educational ideas and practice of John Henry Newman for three decades. Besides various papers and chapters, he has published three books: A Catholic Eton? Newman’s Oratory School (2005) a study of the foundation and early life of the first Catholic public school in England; The ‘Making of men’: the Idea and reality of Newman’s university in Oxford and Dublin (2014); and Conscience before conformity: Hans and Sophie Scholl and the White Rose resistance in Nazi Germany (2018). The latter is a study of the cultural and religious background of the White Rose students which brings out the influence of Newman and others. He has also completed a critical edition of Newman’s Dublin university papers, which were published posthumously in 1896, My Campaign in Ireland, Part I (2021). His critical edition of My Campaign in Ireland, Part II appeared in 2022 along with a festschrift for the great Newman scholar Ian Ker entitled Lead Kindly Light. Essays for Ian Ker.

Conscience Before Conformity

Tells the story of German students who dared to speak out against Hitler and the Third Reich, and died for their beliefs. Operating under the name of the White Rose, they printed and distributed leaflets condemning Nazism and urging Germans to offer non-violent resistance to the ‘atheistic war machine’. These modern-day heroes were deeply influenced by intellectuals they met in secret, and by the writings of the great Christian thinkers.