Dr. Brigitte Maria Hoegemann FSO

Long before the Anglo-Catholic Oxford don actually saw the city, its name must have resonated with John Henry Newman, evoking not just images of the ancient city, kingdom, republic and empire, its history of three thousand years, its rise and the fall, but also its huge claim to power and its unique culture of antiquity both pagan and Christian. Rome was not only a subject of special interest to the young Oxford student, but also the visible centre of the Catholic Church from the time of the apostles. Yet the don still had the conviction, learned as a boy at Ealing, that the Christian faith in Rome had over time become so corrupt as to be the work of Antichrist. The mere name of the city aroused in Newman notions, emotions and convictions both happy and painful. He describes an Anglican looking down on the city, who remarked: “the Christian can never survey (it) without the bitterest, the most loving and the most melancholy thoughts.”[1]

Long before the Anglo-Catholic Oxford don actually saw the city, its name must have resonated with John Henry Newman, evoking not just images of the ancient city, kingdom, republic and empire, its history of three thousand years, its rise and the fall, but also its huge claim to power and its unique culture of antiquity both pagan and Christian. Rome was not only a subject of special interest to the young Oxford student, but also the visible centre of the Catholic Church from the time of the apostles. Yet the don still had the conviction, learned as a boy at Ealing, that the Christian faith in Rome had over time become so corrupt as to be the work of Antichrist. The mere name of the city aroused in Newman notions, emotions and convictions both happy and painful. He describes an Anglican looking down on the city, who remarked: “the Christian can never survey (it) without the bitterest, the most loving and the most melancholy thoughts.”[1]

In the course of time and his personal development, Newman’s attitude to Rome became simpler and more distinct. He visited the eternal city four times, in the early third, fourth, fifth and late seventh decade of his life. These are used as biographical stepping-stones to trace something of what “Rome” meant in Newman’s life, pointing out some of the main changes in his attitude to the city and the Church. When he visited Rome for the first time, in the spring of 1833, invited by friends to accompany them on a long voyage to Southern Europe, he was a young Oxford scholar, an already famous don of Oriel College, an ordained minister of the Church of England, whose preaching and teaching were influenced by his studies of the Early Christians.

Thirteen years later, in early November 1846, he arrived, having been a Roman Catholic layman for just over a year, to prepare for his ordination to the priesthood at the Collegio di Propaganda Fide and to find out about his further vocation. When he left Rome in early December 1847, he was ready to set up an English Oratory at Maryvale, close to Birmingham on his return.

Another ten years later, from 12th January to 4th February 1856, Dr Newman, Provost of the Birmingham Oratory and Rector of the Catholic University of Dublin was for a short time in Rome “on Oratory business”[2]. Differences in the interpretation of the vocation of an English Oratorian by the two English houses in Birmingham and London made it necessary for him to clarify the matter with the Propaganda Fide and the Holy See.

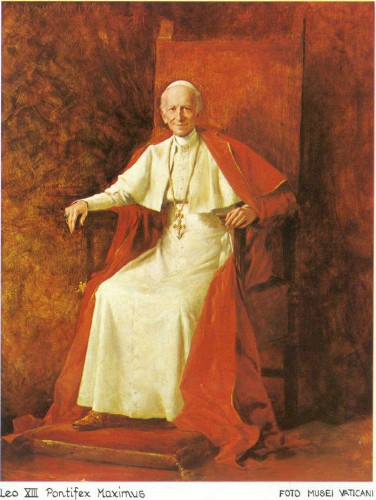

Finally, called by the newly elected Pope, he returned to Rome in his seventy-ninth year, for some strenuous weeks from 24th April to 4th June 1879. On 12th May, in a ceremony at Cardinal Howard’s residence, he received the official biglietto that Pope Leo XIII had raised him to the rank of Cardinal and gave his famous Biglietto Speech; on May 15th, Leo XIII honoured him with the Cardinal’s hat.

I First Impressions of Rome (1833)

1. Rome is a wonderful place – Rome is a cruel place

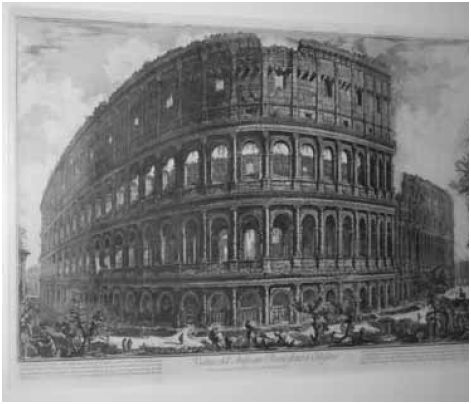

As to Rome, it is the most wonderful place in the world. We do not need Babylon to give us a specimen of the old exertions of our Great Enemy against heaven – (who now takes a more crafty way) – it was an Establishment of impiety -. The Coliseum is quite a tower of Babel – and this is but one out of a number of vast buildings which astound one. Then, when you go into the Museum etc, you get into a second world – that of taste and imagination. The collection of Statuary is endless and quite enchanting. The Apollo is indescribable – its casts give one no notion of it, as an influence – it is overpowering. And the great pictures of Raffaello [sic], tho’ requiring a scientific taste to criticize, come home in a natural way even to the uninitiated. I never could fancy any thing so unearthly as the expression of the faces. Their strange simplicity of expression and almost boyishness is their great charm. – Well then, again after this, you have to view Rome as a place of religion – and here what mingled feelings come upon one. You are in the place of martyrdom and burial of Apostles and Saints – you have about you the buildings and sights they saw – and you are in the city to which England owes the blessing of the gospel – But then on the other hand the superstitions; – or rather, what is far worse, the solemn reception of them as an essential part of Christianity – but then again the extreme beauty and costliness of the Churches – and then on the contrary the knowledge that the most famous was built (in part) by the sale of indulgences – Really this is a cruel place (LD III, 240/241)[3].

When writing this sketch on 7th March 1833, Newman was on a long voyage with good friends. Archdeacon Froude had invited him to accompany him and his son, Newman’s friend, Richard Hurrel Froude, who needed a change of climate on account of his delicate health. They had set off on 8th December 1832 in the Hermes, a military supply ship bound for the British garrisons in the Mediterranean, that also had comfortable facilities for passengers on board, calling first at Gibraltar, thence to Malta, where they spent a month, before arriving via Naples in Rome in the evening of 2nd March. Newman wrote many letters from the Eternal City, where they stayed all through March and the first week of April 1833.

In most of these letters he puzzles the reader with his contrasting, even contradictory comments when summing up his impressions, demonstrating the complex nature of his initial reactions. In the sketch above he distinguishes three main views of Rome. There is first of all the Ancient city and Empire, which Newman brings to his reader’s mind less in its political power and importance than in “the heathen greatness”(249) or the revolt of pagan mankind against the one and eternal God – as conjured up in the visions of Daniel. He describes the Coliseum as the tower of Babel, thus comparing “the hateful Roman power” with Babylon or “the fourth beast of Daniel’s vision and the persecutor of the infant Church” (253). Another example from his letters from Rome brings that out even more clearly:

The first notion one has of Rome is as of the great Enemy of God, the fourth monarchy – and the sight of the city in this view is awful… the immense size of the ruins, the thought of the purposes to which they were dedicated, the sight of the very arena where Ignatius suffered, the columns of heathen pride with the inscriptions still legible, the Jewish candlestick still perfect in every line on the arch of Titus, brand it as the vile tool of God’s wrath and again Satan’s malice. (231)

The first notion one has of Rome is as of the great Enemy of God, the fourth monarchy – and the sight of the city in this view is awful… the immense size of the ruins, the thought of the purposes to which they were dedicated, the sight of the very arena where Ignatius suffered, the columns of heathen pride with the inscriptions still legible, the Jewish candlestick still perfect in every line on the arch of Titus, brand it as the vile tool of God’s wrath and again Satan’s malice. (231)

The second view of Rome is that of a world of exceptional beauty. Newman experiences with delight the “intellectual beauty in the scenery” (240) of Rome, he mentions famous examples of Ancient sculpture and of Renaissance painting[4], he speaks of the beautiful churches, about the amazing bridges, the fountains and other outstanding samples of architecture, sharing with his correspondents this so different and “fresh world”, a world “of taste and imagination” (240). The way in which Newman captures the lively charm of the two fountains in the Piazza of St. Peter is enchanting and may serve here as an example. He compares them to “two graceful white-ladies arrayed in the finest and most silvery dresses”.

There is a highest jet in the middle and it is surrounded by a multitude of others, so contrived all, that in falling they do not form a stream or look at all like water, but are changed into the finest and most impalpable spray circling round the jets, like the plumage of a swan or as I say the muslin of the white lady’s dress. This dashes against a ledge, and then against another; – so that the whole effect is such as I token by way of comparison – for describe the effect I cannot. When the wind takes them, it is like muslin waving about. (264)

Thirdly, he speaks of Rome as a place uniquely marked by its Christian history and the presence of Christianity. Yet the witnesses of this history evoke in him awe and anger. He experiences awe at the sight of the tombs of the early martyrs, or when remembering his gratitude for St Augustine who brought the faith to England, at the tomb of Pope Gregory I.

Yet, other sights make him angry. He cannot fully enjoy the beauty of St. Peter’s, as it reminds him of the business with indulgences. And then there are the many statues of Saints in the churches and in the streets he is passing through, and not just the statues, but candles before them, people who kneel before them, signs that speak to him of superstitions, and even of “the solemn reception of them as an essential part of Christianity” (241).

When offering his third view of Rome: the city “as a place of religion”, notions, impressions, and thoughts, qualifying, opposing, even contradicting one another, follow so quickly upon each other, that Newman no longer forms full sentences, but just names, whatever emerges into his consciousness, in this way communicating to the reader his “mingled feelings” evoked by the sights and his interpretation of them.

Yet, however harsh some of his comments and judgements are, primarily evoked by the impression which the gigantic ruins and what he associates with them made on him, the constant refrain in his letters to friends and family is his praise of the eternal city: “Rome … is of all cities the first, and … all I ever saw are but as dust, even dear Oxford inclusive, compared with its majesty and glory” (230) – “Rome grows more wonderful every day” (231).

During his first visit to Rome, Newman had not only all his senses open to the sometimes awe-inspiring, sometimes light and charming beauty of the place, but he also suffered when recognizing what to him were manifestations of Antichristian features in what he called ‘the Roman system’, if not the work of Antichrist[5] himself in the Roman Catholic Church.

2. The Catholic System most loved – the Roman Catholic System loathed

In some of his later letters from that first visit, Newman developed his third view of Rome, the central seat of the Roman Catholic Church, as a symbol of its system. “As to the Roman Catholic system, I have ever detested it so much… that I cannot detest it more by seeing it, tho’ I may be able to defend my opinion better and to feel it more vividly, – but to the Catholic system I am more attached than ever”(273). He actually suggests that the 19th century Catholic Rome is “somehow” still “the only remnant of the four great Enemies of God – Babylon, Persia, and Macedon have left scarce a trace behind them – the last and most terrible beast lies before us as a subject for our contemplation, in all the visibleness [sic] of its plagues” (248/9). He declares:

I cannot quite divest myself of the notion that Rome Christian is somehow under an especial shade as Roman Pagan certainly was[6] – though I have seen nothing here to confirm it. Not that one can tolerate for an instant the wretched perversion of the truth which is sanctioned here, but I do not see my way enough to say that there is anything peculiar in the condition of Rome – and the clergy, though sleepy, are said to be a decorous set of men. (258)

The cautious reservation and prudent restraint, to which Newman submits these thoughts and opinions on Roman Catholicism, once he is in Rome and has first hand experience of it, are typical of him. His attitude allows the assumption that in spite of the fact that he was busy developing his, so to speak, inherited negative notions and critical opinions of the Roman Catholic Church into a theory, he kept, at the same time, his mind and heart open – not only to a possible new vista, but to the intervention of Providence.

Newman is fascinated by his discovery in many of the churches in Rome, “the materials and buildings of the Empire” were turned … to the purposes of religion. Some of them are literally ancient buildings – as the Pantheon, and the portion of the Baths of Diocletian which is turned into a church. And all – St Peter’s, St John Lateran, etc. – are enriched with marbles, etc., which old Roman power alone could have collected. (235)

That became almost symbolic of the Roman Catholic Church for Newman, which interpolated more and more deformations amid the great Christian truths. The Church seemed to fail in guarding Christian teaching and the life of Ancient Christianity that he loved so much from the influences of the surrounding pagan world. The notion that Rome, Pagan or Christian, the Ancient Empire or the Roman Catholic Church as an institution, was and will be under the wrath of God was nourished by Newman’s prejudice, harboured since his early boyhood. His Protestant conviction was, that Rome is a church system which, by being centred on the Pope, is centred on the Antichrist. Thirty-one years later, Newman will describe in his Apologia[7] the slow process of overcoming that core prejudice held against the Roman Catholic system of faith by Protestantism. In the second chapter of the re-ordered second edition of the Apologia (1865), Newman recalls that from the age of fifteen, he knew and defended dogma as the fundamental principle of religion and believed in a visible Church with sacraments, rites and an episcopal system. But he also stresses that at the same time, he firmly believed “the Pope to be Antichrist“, still preaching on that conviction ten years later, at Christmas 1824.

He relates that through the influence of Richard Hurrel Froude and of Keble, but more so through his repeated, ever more thorough studies of the Fathers of the Church he lost some of his bitterness concerning the Papacy and Romanism: In 1822/23 he spoke less of the extreme Protestant conviction that the Pope takes the role of Antichrist, but still claimed that by the Council of Trent the Roman Church was “bound up with the cause of Antichrist“. Later again, he was still convinced that the Roman Church was “one” of the “many antichrists” whom St. John foretold; but finally that opinion was replaced by the even milder one: that it has something “very Antichristian or “unchri stian” about it (APO II, 52, 64). Gradually, he was to develop more “tender feelings towards” the Roman Catholic Church, especially for her “zealous maintenance of doctrine, for the Apostolic “rule of celibacy” and other faithful agreements with Antiquity (APO II, 54; 65). Yet, in 1833, he still maintained his negative judgment against the Roman Church as an institution (APO II, 54; 65f)[8].

With such convictions in heart and mind, Newman travelled with the Froudes through Italy. No wonder then that they, as he remembered in 1864, “kept clear of Catholics throughout” their tour (APO I, 32; 48), and tried to keep away from Roman Catholic life. All the more important is it to look at the few occasions, when he did come in touch with the living Roman Catholic faith in Italy: when attending a Ponti – fical Mass, visiting some churches and shrines, meeting some priests, and observing some young seminarians.

In one of his letters[9] he told of a Church function, which he had attended in Sta. Maria sopra Minerva on the Feast of the Annunciation[10]. After describing in some seven hundred words the pomp, the show, the luxurious altar dressings and vestments, the appearance of the Sovereign Pontiff and of the religious “court of Rome” with all the sumptuously dressed cardinals and many priests, the manifold and numerous ceremonies, he simply states: “Besides, Mass was celebrated.” After a further three hundred words of description and comment, inevitably leading up again to Daniel’s vision of the four beasts and the solemn declaration that the Roman Church united itself with the enemy of God, he concludes:

And yet as I looked on, and saw all Christian acts performing, the Holy Sacrament offered up, and the blessing given, and recollected that I was in church, I could only say in very perplexity my own words, ‘How shall I name thee, Light of the wide west, or heinous error-seat?'(232)[11], – and felt the force of the parable of the tares – who can separate the light from the darkness but the Creator Word who prophesied their union? And so I am forced to leave the matter, not at all seeing my way out of it. – How shall I name thee? (268)

For the first time ever, he attended Mass, and it was a highly festive one with much going on to distract him from the central mystery. He describes at length what fuelled his dislike and detestation. Having, however, gone through that experience, he cannot but recognize and acknowledge the wheat among the weeds. Remembering the Lord’s recommendation in ‘the parable of the tares’, he confesses his perplexity, acknowledging that it is God’s due alone to separate the light from the darkness. He signals that he is not the one to see his way out of that difficult matter. He quotes two lines from his first poem on Rome. Repeating the first few words, he changes them into an outcry coming from his heart, a true question addressed to the Roman Church demanding an answer: “How shall I name thee?”

He mentions in the Apologia that in Sicily he was most im – pressed by the shrines and the noble churches, as well as by the devotion of the people. He remembers “the comfort” he had received in visiting the churches and recalls especially how the singing in a lonely church in the wilds of Sicily attracted him when on a stroll around six o’clock in the morning. How astonished he was to find out at that early hour that the church was crowded. He adds: “Of course it was the Mass, though I did not know it at the time” (APO II, 53f; 65).

He and the Froudes met but a few priests on their journey, the Dean of Malta, with whom they talked about the Fathers of the Church, and Abbot Santini in Rome, who furnished Newman with the Gregorian chants, and also Dr. Wiseman, then Rector at the English College, whom they heard once preach and on whom Newman called twice before leaving Rome. The only other priest he met in Italy was the one who came to his sickbed in Sicily. Yet, Newman remarks on the young seminarians he saw in Rome: “I feel much for and quite love the little monks of Rome, they look so innocent and bright, poor boys” and again when he speaks of the “children of all nations and tongues” who at the Propaganda Fide are educated “for missionary purposes” (273, 279). In spite of his conviction from the age of fifteen that the Lord had called him to a celibate life to be free for His claim on him for the good of many (APO I, 7; 28), and in spite of the fact that in the Apologia he remembers to have had early on respect for the Apostolic rule of celibacy as it was maintained in the Roman Church, his playful comment, “poor boys” seems to imply a criticism. In a letter, written just a few days later, he speaks, indeed, of “the custom of ‘forced celibacy of the Clergy'” (289). He obviously does not yet understand that if God calls someone to priesthood or to consecrated life and if that person in free will obeys His call that supernatural response in faith, hope, and love enables them, with the grace of God, in free selfgiving to follow the example of Jesus Christ, who lived a celibate, virginal life among us. Newman could not have imagined at that time, that some thirteen years later, at the age of forty-six, he would sit among the young seminarians of the College of Propaganda, attending their lectures in preparation for priesthood.

Looking back to his first experience of the city of Rome, only days after he had left the city, which he was convinced he would never see again, he sums up his experience:

Rome is a very difficult place to speak of from the mixture of good and evil in it – the heathen state was accursed … and the Christian system there is deplorably corrupt – yet the dust of the Apostles lies there, and the present clergy are their descendants. (287)

And again:

Oh that Rome were not Rome; but I seem to see as clear as day that a union with her is impossible. She is the cruel Church – asking of us impossibilities, excommunicating us for disobedience, and now watching and exulting over our approaching overthrow. (284#) The mere tone of his exclamation, the identification of Rome and Church, the fact that he claims that the Roman Church is “excommunicating” Anglicans of the 19th century and that he speaks of demands which she has on them that cannot possibly be fulfilled, show how deeply he suffers from the centuries-old wound of disunity. Less than ever is he able to think about the Anglican Church without seeing it in relation to the Church from which it had separated. His assumption that the Catholic Church expects the imminent overthrow of the Church of England and rejoices in the prospect, speaks volumes. In the Apologia, Newman recalls his farewell visit to Wiseman. The Rector had kindly expressed his hope to see them again in Rome, and he answered, “with great gravity: ‘We have a work to do in England'” (APO 34; 50). That solemn expectation of a mission waiting for him in England assumed the character of an existential conviction and need during his serious illness in Sicily. He was convinced that he would not die, crying out: “God has work for me yet!”[12]. On his return to Oxford, he heard Keble preach the Sermon On National Apostasy on 14th July 1833, and had the strong sense that this was the beginning of a movement of revival in the Anglican Church. Newman recognized the Oxford Movement as “that work which I had been dreaming about, and which I felt to be so momentous and inspiring” (APO 43; 57). Only very gradually did he realize that what he had meant to be his own work of strengthening the Anglo-Catholicism in the Church of England, thus fighting the forces of liberalism in re-ligion, had been taken out of his hands. He accepted step by step that God was doing His work in him and wanted to do more through him, leading him to ask to be received into full communion with the Catholic Church.

II At Home in Rome (1846-1847)

1. Advised to Prepare for Priesthood in Rome

When Newman had embraced the Catholic Church as the true heir of the Early Church of the Fathers and had been received at Littlemore into full communion with the Catholic Church by the Italian Passionist Padre Domenico Barberi[13], it was Mgr. Wiseman who confirmed him[14], with St John, Walker and Oakeley on All Saints Day 1845 at Oscott. The former Rector of the English College in Rome, whom Newman had met in 1833, had in the meantime become the President of the new Oscott College near Birmingham and the Coadjutor to the Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District. He offered Newman and his fellow converts old Oscott, the former Seminary of the Midland district, “without rent, stipulations, control, or responsibility of any kind”(79).

In February 1846, Newman left Littlemore for Maryvale, his new name for Old Oscott, for another spell of shared life with some of his now Catholic friends. It seemed ideal as “a place of refuge”, as they “had still to find out the vocation of each and all”. The position of the house seemed to be just right, only a few miles from Birmingham, which at that time was one “of the chief nurseries of Catholicism” (79). Though Newman had lived at Oriel College many years beside the chapel, with an entrance from his flat into the organ loft, it was totally different for him to live in Maryvale wall-to-wall to the Lord in his Eucharistic presence in the tabernacle:

I am writing next room to the Chapel – It is such an incomprehensible blessing to have Christ in bodily presence in one’s house, within one’s walls, as swallows up all other privileges and destroys, or should destroy, every pain. To know that He is close by – to be able again and again through the day to go to Him. (129#) He could actually open a window in that wall, which allowed him to look down into the chapel and see the tabernacle below without leaving his room.[15] This brought home to him the realness of the Catholic faith, where everything falls into place, joy and pain, by the grace of the personal, Real Presence and clo seness of the Lord.

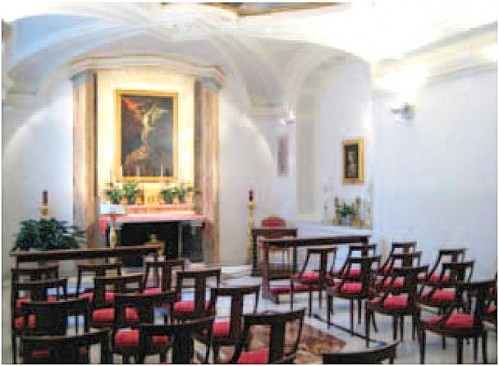

Chapel at Maryvale

Chapel at Maryvale I could not have fancied the extreme, ineffable comfort of being in the same house with Him who cured the sick and taught His disciples, as we read of Him in the Gospels, in the days of His flesh. (131)

It was providential that the Holy Father, Gre gory XVI, sent him and the small community a silver crucifix and a splinter of the True Cross. Cardinal Fransoni, the Prefect of the Propaganda Fide, added a personal letter to the two precious gifts. Their personal interest in him touched Newman; yet, he was moved even more by the “singular coincidence”, as he wrote to Miss Giberne, “that the certificate of the grant of the sacred Relic is dated on the date that No 90[16] came out 5 years ago – and the news of it came to me on the anniversary of the Heads of the Houses bringing out their manifesto against it – so that the process of condemnation was just as long as the time it has taken to do me honour” (139). In the thoughtful personal gesture of the Pope, Rome had come to Maryvale, long before Newman left Maryvale for Rome. Around Easter, in April 1846, less than two months after Newman’s move from Littlemore to Mary vale, Mgr. Wise man advised him to go to Rome for a year of studies at the Collegio di Propaganda Fide. This was, as Newman said, “simply my own act”, and yet he “wished to leave the whole thing to him”. The choice of the College was Wiseman’s response to Newman’s wish for “a regular education” (152), the wish to go somewhere, where he “might be strictly under obedience and discipline for a time” (283).

Dr. Nicolas Wiseman 1802-1865 Rector of the Venerable English College in Rome later Cardinal and Archbishop of Westminster

Dr. Nicolas Wiseman 1802-1865 Rector of the Venerable English College in Rome later Cardinal and Archbishop of WestminsterOn 1st June 1846, the vigil of Trinity Sunday, John Henry Newman, Ambrose St. John and three or four of their group[17] received Minor Orders and the tonsure in the chapel of Oscott. It was not until 9th June that they learned that it had been the very day Pope Gregory XVI died. Newman, who had expected to go to Rome with Dr. Wiseman by the end of the month, was content that his departure was deferred until the autumn.

Soon after Pius IX was elected on 16th June, the new Pontiff, too, sent a thoughtful sign to Newman, who on 21st July 1846 wrote to Dalgairns: “The new Pope sent me his blessing, and I hear that the last thing he was speaking of before going into the conclave was about Wiseman and me” (212)[18]. He also learned from Dr Wiseman in August, that Cardinal Fransoni had assured him that the Propaganda was ready to comply with whatever Newman might wish for at the college; they wanted “to help the movement” (218). It was Wiseman’s suggestion that two from Maryvale should go; Ambrose St John was to be Newman’s companion at the Propa ganda (219).

2. At Home in the Roman Faith – The Catholic Religion – a Real Religion

After a short stay in Paris, where he also visited the shrine at Notre Dame des Victoires in gratitude for prayers offered there for him by a Fraternity of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, which had the image of the Miraculous Medal for its badge[19], Newman and St John spent five weeks in Milan. His letters give a most lively account. He had come home, a Catholic, to the place to which St Athanasius had come “to meet the Emperor, in his exile”; to the See and the tomb of St Ambrose; to the place, where St Monica sought her son; the place of the baptism of St Augustine[20]. He got to know and to love, and to be at home, too, with the great Archbishop St Charles Borromeo[21], who, in the strength of Christ, resisted “that dreadful storm under which poor England fell”, saving his country from Protestantism. Newman went almost daily to kneel and pray at his tomb, convinced to find in this great Saint of the Counter-Reformation a special helper for his future mission in England. In this simple act of devotion, he affirmed the fact that the Catholic Church of all ages had become his home. More than by anything else, the convert was touched by the presence of the Blessed Sacrament in all the churches. It became a main topic in his letters. In Maryvale, he had had the personal experience of actually living with the Lord under one roof. Now in Milan, the experience ‘I live with God’ was broadened and changed to the experience: ‘Wherever I enter a Catholic church, the Lord is waiting for me’. He wrote:

It is so very great a blessing to be able to go into the churches as we walk in the city – always open with large ungrudging kindness – full of costly marbles to the sight, and shrines, images, and crucifixes all open for the passer-by to make his own by kneeling at them – the Blessed Sacrament everywhere. (251)

On his first trip through Italy in 1833, Newman had not ob – served the tabernacle light, nor known its meaning, as he did not understand or attempt to understand Mass (131). But now he saw the sanctuary light flicker and invite him from within the churches he walked by:

It is really most wonderful to see this Divine Presence looking out almost into the open streets from the various Churches, so that at St Laurence’s we saw the people take off their hats from the other side of the street as they passed along; no one to guard It, but perhaps an old woman who sits at work before the Church door, or has some wares to sell. (252)

He was overwhelmed that the Blessed Sacrament is, as it were, “ready for the worshipper even before he enters” (254). By the visible omnipresence of the Eucharistic Lord, if it could be named visible, Newman experienced also the unity of the Church:

There is nothing which has brought home to me so much the Unity of the Church, as the Presence of its Divine Founder and Life wherever I go – All places are, as it were, one – while the friends I have left enjoy His Presence and adore Him at Maryvale, He is here also. (254)

Something else was brought home to him in Milan by the Real Presence of the Lord in the Eucharist and the way the faithful people react to it: Newman realized that the Catholic faith is a real religion, not just a belief among others. He realized that going to church marks the lives of those who live up to their faith, be they educated or not, rich or poor, old or young. The faith gives their lives a special character, which makes them feel at home in cathedrals, in churches or chapels. It makes them take their religion home after the services – in so many forms of devotion, which give their days a structure, linking the natural events of everyday life to the Creator, the Saviour, and the Sanctifier, to the Holy Trinity. There are many signs, symbols and images reminding them that they live in the presence of God, wherever they are, in churches as well as in their homes, at their work places and where they meet their friends. Newman had long realized that faith comes from hearing, listening always more carefully to the message of the Gospels and the teachings of the Apostles, as well as that of the Fathers of the Church. Now he realized even more that faith becomes a real, a transforming strength in the life of the Christian by being lived: primarily in the simple, set acts of responding to the presence of Christ: in holy Liturgy, in the divine service of Holy Mass and in the other sacraments, then – in the strength of these – also in the actualities of daily life. In Newman’s own words:

I never knew what worship was, as an objective fact, till I entered the Catholic Church, and was partaker in its offices of devotion, so now I say the same on the view of its cathedral assemblages. (253)

Few will forget the way Newman describes the life in a Catholic cathedral:

… a Catholic Cathedral is a sort of world, every one going about his own business, but that business a religious one; groups of worshippers, and solitary ones – kneeling, standing – some at shrines, some at altars – hearing Mass and communicating – currents of worshippers intercepting and passing by each other – altar after altar lit up for worship, like stars in the firmament – or the bell giving notice of what is going on in parts you do not see – and all the while the canons in the choir going through [[their hours]] matins and lauds [[or Vespers]], and at the end of it the incense rolling up from the high altar, and all … lastly, all of this without any show or effort, but what every one is used to – every one at his own work, and leaving every one else to his. (253)

In Milan, Newman learned what it meant to be at home in Rome, at home in the Roman Catholic faith and Church. When he was still an Anglican, he had “studiously abstained from the Church services in Italy”. Now, thirteen years later, he attended them and truly “entered into them” (253).

3. Preparing for Ordination to Priesthood in Rome and Finding a Roman Vocation for England

It seemed providential to John Henry Newman that he and Ambrose St John found Pius IX celebrating Mass at the Confessio in St Peter’s[22], when they visited the Basilica for the first time after their arrival in Rome:

… the first morning I was here at St Peter’s – we went to say the Apostles’ Creed at St Peter’s tomb, the first thing – and there was the Pope, at the tomb saying Mass – so that he was the first person I saw in Rome and I was quite close to him. People say such a thing could hardly have occurred once in a century, for no one can celebrate there but he, and he went by accident (in private) that morning – no one knew he was going. (282)

Mary Giberne painted New man and Ambrose St John at the Propa ganda College on 9th June1847

Mary Giberne painted New man and Ambrose St John at the Propa ganda College on 9th June1847The College of Propaganda did their utmost to show their eminent student and his friend their respect and to give the converts a true home in a Catholic community. Newman describes in his letters the great care taken by Cardinal Fransoni, the Prefect of Propaganda, Mgr Brunelli, the General Secre tary of Propaganda and Father Bresciani, the Rector of the Collegio di Propaganda to make him feel at home by making “every thing suitable to English habits.”(270)

We are certainly most splendidly lodged … much better off than even in England. They have cut off by a glazed partition the end of a corridor, and thus united two opposite rooms, the intercepted portion of the gallery being at once a room of passage, and of reception for strangers. (269).

In a few of his letters he describes “the very nice rooms” (268) and what they contain; everything seems to be new: the furniture, the wallpaper, the curtains, the bedclothes and sheets, even the priedieus, the writing tables, and the crucifixes. Another time, when he tells how they found their beds made up, the reader almost sees his smile when he speaks about the absurdity to be thought of having curtains around his bed in England (273). “We are treated as if we were princes, much to our distress”, he writes (272), and again with humour “like wax dolls or mantle piece ornaments” (273). He affirms that they are “anticipating all our wants in the most provoking way” and again he adds with good humour: “so that we were obliged today to smuggle some things in, in our pockets” (269). In addition to the very good meals, they are served tea in the evening, stoves are put into their rooms (276), and they receive “a key of the library” (269) the very first day. They were quite moved – Newman mentions it several times in his letters – that their windows at the Propaganda looked down on the church of San Andrea delle Fratte, where Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal had appeared to Alphonse Ratisbonne on 20th January 1842 (269)[23]. At Littlemore, Newman realized that his Oxford life had been under the protection of the Blessed Virgin; he renamed Old Oscott Maryvale; a Miraculous Medal and a prayer campaign for Newman in Paris played a role on his way into the Catholic Church. They must have recognized their closeness to that place of her apparition as a sign of God’s loving providence. Mary Giberne’s[24] painting shows that awareness of Our Lady’s protection, too. She depicts Newman and St John, sitting in one of their rooms in the Collegio, and Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal stands in the middle behind the two priests, as if watching over them[25].

Newman was touched by the kindness he met in Rome and only worried, as it seemed to him that his new friends felt respect for someone who largely remained a stranger to them, “some imagination of their own which bears my name” (294). But such thoughts brought him closer to God as the one who has known him and has always shown him his love, guarding his ways. Thus he could write:

It is so wonderful to find myself here, in Propaganda – it is kind of a dream – and yet so quiet, so safe, so happy – as if I had always been here – as if there had been no violent rupture or vicissitude in my course of life – nay more quiet and happy than before. I was happy at Oriel, happier at Littlemore, as happy or happier still at Maryvale – and happiest here. At least, whether I can rightly compare different times or not, how happy is this very thing that I should ever be thinking the state of life, in which I happen to be in, the happiest of all. There cannot be a more striking proof how I am blest. (294)

The eminent Anglican theologian, thinker and preacher, then the author of already a good number of books, co-author or editor of even more, leader of the Oxford Movement, and his learned friend Ambrose St John, both Oxford graduates, now converts, found themselves among the young and very young foreign seminarians and young priests, most of them from the mission countries of the Church. Among the 120 to 150 resident students (277, 296) 32 languages were spoken. Newman mentions “Indians, Africans, Babylonians, Scots, and Americans” (272), and again “Chinese… Egyptians, Albanians, Germans, Irish” (283), he and Ambrose St. John being the only English students.

In an early letter he had expressed his disappointment about finding little theology and philosophy in the then existing theological schools throughout Italy. He hoped that the Pope would do something about the fact that Thomas was loved and venerated as a Saint, but not taken as an authority. Quoting one of the Jesuit Fathers, he wrote: “They have no philosophy. Facts are the great things, and nothing else. Exegesis, but not doctrine” (279).

Until Christmas 1846, however, Newman and St John voluntarily (“This too was all left to ourselves.”) attended with the seminarians three lectures on five days a week, “two dogmatic, and one moral” (273). When they ceased going, they only did what the professors at the Collegio di Propaganda had expected them to do from the very beginning. In a letter to one of his group at Maryvale, interested in studying at the Collegio, Newman explains why at his time a post-graduate student was not catered for at the Propaganda. The teaching, its method even more than its content, was addressed to young beginners only.

The lecturers are men quite up with their subject, but the course takes four years …lecture after lecture “to drawl through a few tedious pages – … necessary for boys, but not for grown men[26].

The two Oxford men replaced the lectures by personal studies, deliberating whether to take a doctorate from the Propaganda. Newman, however, considered his first duty to make known his theological thinking, especially on faith and reason. It had brought him into the Church and seemed to him to be Catholic. He could see that the phraseology needed to be altered here and there to facilitate the understanding in a Catholic context of different academic traditions. He therefore wrote an explanatory introduction to the planned French translation of six of his Oxford University Sermons, giving background knowledge of his thinking on faith and reason to Catholic readers[27]. Before the beginning of March, he also translated four “dissertations” from his Athanasius into Latin for publication (60)[28] to counteract a criticism, which was passed on from one of the colleges in Rome to the other, that a “mere theorist” had written the Essay on Development (60). Those dissertations gave evidence to the fact, that he had, indeed, “studied, analysed, sorted, and numbered” the phenomena of the documents of ancient theology, as a critic ought to do[29].

He and St John attended the monthly disputation at the Collegio Romano, at the invitation of the Rector, Fr Passaglia (61). They participated regularly in the theological meetings at the English College, invited by the Rector, Dr Grant (57). Newman was also content to discuss some of his ideas on faith and reason and on the development of doctrine with Fr Perrone[30], then quite a celebrity in Rome.

Above all, the two converts allowed time for God to show them in which way their group was to serve the Church in England. Dr. Wiseman had already encouraged them at Maryvale to consider the Oratorian vocation. Soon after their arrival in Rome, they contacted the Oratory, making friends with the learned Fr Theiner. From now on, they attended now and then services in the Chiesa Nuova, calling at the Oratory house. They informed themselves about the rule and the history of St Philip’s Oratory, but they also looked at other Congregations. Newman had great respect for the self-denying life of the Jesuits, “the most wonderful and powerful body among the Regulars” (25), for their holiness and selfless devotion (111), which he experienced first hand at the Collegio di Propaganda. He thought highly of the Passionists, so “peaceful” and of the Capuchins, so “cheerful”, though they seemed to him to be the two severest Orders (62). They read the rule of the Redemptorists (7f) and were in contact with the Franciscans (10f) and the Rosminians (5). He took an interest in the Dominicans in Rome and later developed a lifelong love for the Benedictines, yet, he could not imagine himself becoming a monk or a modern Regular like the Jesuits. He was aware that it would not only mean at the age of forty-six to give up “property” and “take to new habits” but lastly, to part with his whole former life, which had not just been his, private to him. His name, his person, his books were known to many whom he had never met in person. As a Regular, he would cut off all this, and if he were still speaking and writing, people would not know whether he was passing on what was thought in his community (as “a sort of instrument of others”) or whether he was speaking his own words. With one word, he needed what he called “continuation, as it were, of my former self”[31].

On the one hand, he did not want to become a monk, on the other hand, he thought they had “a calling to a life more strict than a secular’s”. There the Oratorian Rule seemed to him “a sort of ‘Deus ex machina’” (16). On 17th January, he began a letter to Mgr Wiseman:

“It is curious and very pleasant that after all the thought we can give the matter, we come round to your Lordship’s original idea, and feel we cannot do better than be Oratorians.”(19f) That was also the first day of a novena of daily pilgrimages to St Peter’s from the eve of the Feast of St Peter’s Chair, then on 18th January, to that of the Con – version of St Paul on 25th January – for light in that matter. On 21st February, Newman’s birthday, Mgr Brunelli, the Secretary of Propaganda, gained the Holy Father’s approbation of Newman’s calling to introduce St Philip’s Oratory to England. Pope Pius IX expressed his joy by offering the Monastery of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme to the future English Congregation of St Philip Neri for the first part of their noviciate from July to December1847 in Rome. This caused Newman to remark that it meant to live in the centre of the Church. St. Helena had not only brought Christ’s Cross from Jerusalem to Rome, but with it earth from Mount Calvary. Santa Croce is Jerusalem in the midst of Rome[32].

One month before they moved to Santa Croce, on St Philip’s day, 26th May, Cardinal Fransoni ordained Ambrose St John and John Henry Newman subdeacons “in his private chapel” (84). On 29th May, they were ordained deacons in St John Lateran by the Cardinal Vicar. On Trinity Sunday, 30th May, Cardinal Fran soni ordained them priests at the Propaganda. This must have been in the Propaganda church (84), as “all the students”[33], were present and they had the organ play. After the ordination, they went to see the house in Santa Croce. On Corpus Christi, New man celebrated his first Mass at the Propaganda, in the Jesuits’ Chapel, on the altar above the shrine of St Hyacinth, not far from his room.

Recently the altar, where Newman had celebrated his first Mass and which had been moved to the new Collegio Urbano on the Gianicolo, was returned to the Propa – ganda Fide on the Piazza di Spagna and a chapel was set up again for the praise of God and in hom age to John Henry Newman.

Recently the altar, where Newman had celebrated his first Mass and which had been moved to the new Collegio Urbano on the Gianicolo, was returned to the Propa – ganda Fide on the Piazza di Spagna and a chapel was set up again for the praise of God and in hom age to John Henry Newman. They moved to Santa Croce on 28th June, and on the next day, Newman celebrated the Mass for the Feast of Peter and Paul. In the evening all of them walked to St Peter’s as in those nine days in January, this time in thanksgiving.

In the centre of the Church, in Santa Croce, Newman would more and more find the heart of St Philip, and under his guidance the Heart of Jesus, the light of his soul, whom he adored in the Eucharist. In the grace of his vocation, and in the sign of the Cross he would become a Father of souls in the new Oratory of St Philip. When Newman left Rome in December, he carried the brief with him.

Of Pius IX Newman said:

“He is a vigorous man, with a very pleasant countenance, and was most kind. So familiar, that when he had told us some story about the conversion of an English clergyman, St. John in his simplicity said:’What is his name?’ – on which he with great good humour laid his hand upon his arm, and said something like ‘Do you think I can pronounce your English names?’ He is quick in his movements, and ran across the room to open a closet and give me a beautiful oil painting of the Mater Dolorosa.” After Newman visited Pope Piux IX, he wrote a letter to F.S. Bowles on 26th november 1846, LD XI, 285.

III Self-giving (1856) and Late Reward (1879)

Even just a glimpse of Newman’s third and fourth time in Rome makes the reader recognize two more aspects of what Rome meant to Newman.

His third trip, once more with Ambrose St John, was undertaken in the immense effort to solve some problems which had developed between the two houses in England concerning the interpretation of the Oratorian rule, before the wound of disunity would start to fester – with long-lasting consequences. That mission was most strenuous for Newman at a time when he was burdened with the double task of the Oratory House in Birmingham and the fledgling Catholic University in Dublin. It was moreover a “business of very great anxiety”. Newman knew that he could not do it in his own strength. On the first day in Rome, he turned the visit to St Peter’s into a midday pilgrimage, walking the whole way from Spanish Place barefoot to the shrine, and that on a cold winter’s day, on 13th January 1856, not known to anyone but to Fr Ambrose[34]. And, indeed, the trip to Rome not only brought clarity to the matters in question, but the Holy Father granted them whatever they had asked for, and more. The way in which Newman had dealt with the difficult matter, travelling to Rome, coming as a supplicant, entrusting everything to God at the Confessio of St Peter, then approaching the Holy Father and other members of the hierarchy in person, manifested his deep faith in Christ and his humble and simple trust in Rome, in the Holy Father and those who carry the ecclesial authority with him[35]. When Newman travelled again and for the last time to the eternal city in spring 1879, the Holy Father had called him. Leo XIII wanted to honour the great Englishman for the good of the whole Church by creating him Cardinal. Newman was one of the first nine Cardinals appointed in his Pontificate, and the Pope liked to refer to him as il mio Cardinale. Providence had been at work. In a visit of Lord Selborne and his daughter in October 1887 he stated in retrospect:

My Cardinal! It was not easy, it was not easy. They said he was too liberal, but I had determined to honour the Church in honouring Newman. I always had a cult for him. I am proud that I was able to honour such a man[36].

His Excellency Gioacchino Pecci had been the Nuncio in Brussels (1843 to 1846), whom Father Dominic Barberi had visited in October 1845[37] on the way from Oxford to a Chapter of the Passionists in Belgium. George Spencer had already found out in July 1844 that the Nuncio was well informed about the Oxford men[38]. Fr Dominic Barberi must have been happy to tell his compatriot about the last events in Oxford and at Littlemore. He had just received John Henry Newman into what the convert called “the one flock of the Redeemer”[39]. Will he not have vividly described how he found “one of the most humble and lovable men” he had ever met at his feet, begging him “to hear his confession and admit him into the bosom of the Catholic Church”[40]? It is a fact that from 1845 onwards, the then Nuncio kept up his lifelong interest in John Henry Newman. Judging from his letters and diaries, Newman may not even have been aware of Pecci’s longstanding interest in him, yet after his election, he quite often mentioned Leo XIII in his letters. On 27th October 1878 he wrote:

I …have followed with great love and sympathy every act which the Papers have told us of him since his elevation, I only wished he was 10 years younger – that he is not, is his only fault”[41].

He found satisfaction in the fact that Pope Leo XIII advised the study of Saint Thomas Aquinas at the Pontifical universities and the seminaries for priests, so much missed by the convert when studying in Rome in 1846/7[42]. He was touched, when in December 1878, Leo XIII sent him his Papal Blessing and a devotional picture from his breviary signed with his name, through a former employee at the French Embassy in Rome, whose confessor Newman had become[43]. Shortly after Pope Leo had been elected, rumours started in Eng land and Rome that Leo XIII would create Newman a Cardinal. Newman did not pay much attention to them, but on 1st March 1879 he wrote to Anne Mozley:

He found satisfaction in the fact that Pope Leo XIII advised the study of Saint Thomas Aquinas at the Pontifical universities and the seminaries for priests, so much missed by the convert when studying in Rome in 1846/7[42]. He was touched, when in December 1878, Leo XIII sent him his Papal Blessing and a devotional picture from his breviary signed with his name, through a former employee at the French Embassy in Rome, whose confessor Newman had become[43]. Shortly after Pope Leo had been elected, rumours started in Eng land and Rome that Leo XIII would create Newman a Cardinal. Newman did not pay much attention to them, but on 1st March 1879 he wrote to Anne Mozley:

I have this very day learned that the offer of a Cardinal’s Hat is to be made to me with the privilege of living still here as before. So great a kindness made with such personal a feeling towards me by the Pope, I could not resist, and I shall accept it. It puts an end to all those reports that my teaching is not Catholic or my books trustworthy, which has been so great a trial to me so long[44].

On the 2nd March, he wrote to Pusey:

If the common reports are true, the present Pope in his high place as Cardinal, was in the same ill odour at Rome as I was. Here then a fellow feeling and sympathy with him colours to my mind his act towards me. He seems to say ‘Non ignara mali etc.’ How can I not supplement his act by giving my assent to it[45].

In his speech on the reception of the Biglietto at Cardinal Howard’s Palace in Rome, his Eminence pointed out:

I have nothing of that high perfection, which belongs to the writing of Saints, viz that error cannot be found in them; but what I trust that I may claim all through what I have written, is this, – an honest intention, an absence of private ends, a temper of obedience, a willingness to be corrected, a dread of error, a desire to serve Holy Church, and, through Divine Mercy, a fair measure of success. And I rejoice to say, to one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion.

He then characterized the liberalism in religion he had been opposed to since his early time at Oxford, and the statements echo in our ears today, one after the other:

….one creed is as good as another … all are to be tolerated, but all are matters of opinion. …Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact; not miraculous. … Religion is a private luxury, which a man may have if he will; but which of course he must pay for, and which he must not obtrude upon others or indulge in to their annoyance.

But then his ultimate confidence in faith that the Word of God has already won made him end his speech with a great consolation and a fervent appeal:

Commonly the Church has nothing more to do than to go on in her own proper duties, in confidence and peace; to stand still and to see the salvation of God [46].

[1] See the discussion by “two speculative Anglicans” aiming at strengthening their Church in: Home thoughts Abroad, published in the British Magazine in the spring of 1836, republished under How to accomplish it in: Discussions and Arguments on Various Subjects, London 1872, pp. 2f.

[2] Ch. St. DESSAIN (ed.), The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman, I-XXXII, London/Oxford, Nelson/Clarendon Press, 1961-2007, vol. XVII, p. 99: From now on abridged e.g. LD XVII, 99.

[3] Unless otherwise stated, the page numbers after the quotations in the text refer to LD III.

[4] He had by then already visited the Vatican Museum for the first time.

[5] Already Martin Luther depicts the Pope as Antichrist, who soon after Gregory the Great started to govern the Church, enthroning himself in God’s temple, claiming authority over the Word of God. Cf. Schmalkald. Art. IV; (2 Thess 2:3-12; Rev 13:5).

[6] A fuller account of this theory is to be found in the letter to Samuel Rickards on 14th April 1833 from Naples, LD III, 287-290 and in Discussions and Arguments, see above, footnote 1.

[7] J.H. NEWMAN, Apologia pro vita sua, 2nd edition 1865, II pp.52-54; 64-65.The Roman number refers to the chapter, the first Arabic numeral to the unified edition, the second to the edition in the Penguin Classics ed. by I. KER 1994.

[8] In 1843 John Henry Newman formally withdrew “all the hard things”, which he had said against the Church of Rome (APO IV, 200; 184).

[9] Cf. LD III, 266-269.

[10] The other two of just three Church services, which he seems to have attended, were the afternoon offices on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday at the Sistine Chapel: “the Tenebrae”

(272).

[11] From his first poem on Rome in a letter to his sister Harriett.

[12] LD IV, 8.

[13] Since 1963 Blessed Dominic Barberi.

[14] In gratitude he took the name of Mary, see LD XI, 23, footnote 1. Unless otherwise stated, the numbers in brackets after the quotations in the text refer now to LD XI.

[15] The window in that room can still be opened, and the sanctuary light glows beside the tabernacle below in the beautifully restored chapel. The Maryvale Institute plans to turn John Henry Newman’s room into a shrine.

[16] Tract Ninety.

[17] This is implied from Newman’s letter to the Earl of Shrewsbury on 23rd Aug. 1846, LD XI, 232.

[18] Cf. letter to Knox, 20th Aug. 1846, (227).

[19] Cf. LD XI, 245, diary, footnote 1; also the footnotes 22 and 23 of this essay.

[20] Cf. (252f).

[21] Cf. (250f).

[22] Cf. Diary in LD XI, Thursday 29th October 1846 (266).

[23] Also e.g. LD XII 23.

[24] Mary Giberne – a lifelong friend of the Newman family, convert of John Henry Newman.

[25] Cf. LD X, 658, footnote 2 and the photograph of Mary Giberne’s painting of Newman and Ambrose St John at the Propaganda College with the information of Fr. Gregory Winterton in: Benedict XVI and Cardinal Newman, ed. by P. JENNINGS, Family Publications, Oxford 2005, p. 83.

[26] LD XII, 48. Interesting in this context is the letter written by Newman to the Rector of the Collegio, LDXII, 88-90.

[27] Cf. LD XII, 5. Unless otherwise stated, the numbers in brackets after quotations in the text refer now to pages in LD XII.

[28] These were his insights related to and published with his translation of Athanasius in the Library of the Fathers.

[29] Loc. cit. On 12th May Newman could give the Rector his copy.

[30] Cf. LD XII, 55 incl. footnote 3.

[31] LD XI, 306 italics by Newman.

[32] Cf. (79).

[33] Cf. (84), footnote 2

[34] According to Fr Neville, see LD XVII,119 footnote 2 referring to My Campaign in Ireland, p. 214.

[35] For details see LD XVII Opposition in Dublin and London October 1855 to March 1857 and the chapters The Oratories in Opposition in: M. TREVOR, Newman: Light in Winter, London 1962, pp.73-84 and esp. 112-128, as well as 129-141.

[36] LD XXIX, 426, Appendix 1. This is not the place to take up the immense difficulties behind the scenes of the elevation of Newman to the cardinalate, much has been written about these affairs.

[37] Not only is that visit mentioned by U. YOUNG, C.P., Life and Letters of the Venerable Father Dominic (Barberi), C.P., Founder of the Passionists in Belgium and England, London 1926, p. 259, and as such in 1975 quoted by DESSAIN and GORNALL in LDXXIX, 426, Appendix 1, footnote 2, , but nine years later Fr. Urban published a letter of Fr. Dominic, written on October 26th 1845, between his two visits to Littlemore, in which he actually speaks of the “Nuncio at Brussels, whom I visited” (U. YOUNG, C.P, Dominic Barberi in England, A New Series of Letters, London 1935, p. 142).

[38] Cf. LD XXIX, 425, footnote 2 .

[39] See for the repetition of this expression the many letters he wrote in the night of Fr Dominic’, the Passionist’s arrival in the first pages of LD XI.

[40] Letter from Tournai, October 1845, U. YOUNG, Dominic Barberi in England, London, 1934, p. 138.

[41] LD XXVIII, 415.

[42] Ioco cit., 431, footnote.

[43] Cf. LD XXVIII, 435, footnote 1

[44] LD XXIX, 50.

[45] LD XXIX, 55/6, footnote referring to Aeneid I 630: Non ignara mali miseris succurrere disco.

[46] M. K. STROLZ (ed.), John Henry Newman. Commemorative Essays on the occasion of the Centenary of his Cardinalate, Rome 1979, pp. 100-102, 105.

The article was first published in: John Henry Newman in His Time, Oxford: Family Publications, 2007, pp. 61-81. It is reprinted here, with some additions by the author, with the kind permission of the publisher.