The great biographer of Newman, a convert from Anglicanism, always inspired fondness in those who reveled in his wit, his bonhomie, his learning, and his very real, if inconspicuous pietas.

With the generous permission of the author Edward Short

Jesus, I hope one day by Thy grace to follow Thee in my person.

To go to heaven is to go to God.

J. H. Newman

Fr. Ian Ker, the leading authority on the life and work of St John Henry Cardinal Newman, died in the early morning of November 5th in hospital in Gloucester, England not far from his home in Cheltenham Spa. A brilliant scholar, apologist, critic and biographer, Fr. Ker wrote what is generally regarded as the definitive life of Newman, as well as many additional books on the saint’s conversion, theology, sermons and spirituality. He also wrote a scholarly life of G.K. Chesterton, showing how the paradoxical convert carried on Newman’s apostolate. Moreover, Fr. Ker published a classic critical account of authors of the Catholic Revival, with chapters on Hopkins, Belloc, Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and Ronald Knox. As one of his fondest friends, Bishop James Conley remarked, Fr Ian’s departing our mortal coil on Guy Fawkes Day must have made for “many smiles in Heaven.”

Born in Naini Tal in India on August 30, 1942, Ian Turnbull Ker was the son of Charles Murray Ker of the India Civil Service and his wife Joan May Knox, the daughter of another official in the India Service who was a first cousin of Ronald Knox. He had two sisters, one younger and one older, though the younger died tragically when still in her twenties. Naini Tal had been set up in the 1860s and 1870s under the Raj as the summer hill station for the North Western Provinces. In 1947, Ian Ker and his parents and two sisters left India after independence was declared and settled in Wimbledon. As Fr Ker recalled, “I arrived in a bitterly cold England at the age of 5 where there was still no central heating (to the disgust of my Canadian-born paternal grandmother) and where wartime rationing was still in force. Apart from a nanny and maid, there were no servants as contrasted with India where there were servants for every possible task.” The English in India often had to employ more servants than they wished, if only because religion and caste limited what any given servant could perform. Being, as he was, a child of the Raj, Fr. Ker had always a certain imperiousness, but also a delicious sense of humor, the absurdities of misrule, whether in the ecclesiastical, political or academic sphere, always appealing to his sense of the ridiculous.

As a boy, Fr. Ker recalled entering into the Sacred Heart Church in Edge Hill, Wimbledon and finding it at once impressive and welcoming. “I remember as a small boy wandering into the cathedral-like Jesuit church out of curiosity and being welcomed by an old Irishman at the back. There were an unusual number of Catholics in Wimbledon in South London, where I grew up, no doubt because there were a Jesuit school and an Ursuline convent school. The service – which of course, being the Tridentine Mass, I didn’t understand – was utterly unlike the middle-of-the-road Church of England matins we attended as a family.” However intriguing Fr. Ker found the Jesuit church, his view of Catholics at the time was conventional enough. “Thanks to history, not religion, lessons at school about Good Queen Bess as opposed to Bloody Mary and to the threatened Spanish Armada, I thought of Catholics as disloyal quasi-foreigners.”

It was his uncle, a Classics don at Trinity College, Cambridge, who recommended that Fr Ker go to Shrewsbury School, whose brightest pupils in the 1960s went to Balliol or Trinity College, Cambridge. That the most famous of Shrewsbury’s Old Boys should have been Charles Darwin gives Fr Ker’s time there an apt twist – the theme of development that would so preoccupy Newman being in the air even when Fr Ker was a schoolboy. From Shrewsbury, Fr Ker duly went to Balliol, about which he was somewhat ambivalent. “Balliol was the pre-eminent college at Oxbridge for Classics and I only got there through excellent teaching and hard work,” he recalled.

I read ‘Mods and Greats’, which in those days oddly encompassed both ancient history and ancient and modern philosophy. I loathed ancient history for the very reason that my Classics school teacher had commended it, the paucity of sources/documents; it seemed to consist of reading endless articles in learned journals of an extremely hypothetical nature (if …, then …); exactly the sort of argumentation I was later to encounter in Biblical studies. After completing Mods and Greats, I was taught by the top scholars in their fields. Gordon Williams (who taught me to think) later occupied the Yale chair in Latin; Russel Meiggs (one of the pre-eminent ancient historians of his time and editor of J. B. Bury’s History of Greece); and R. M. Hare, then the pre-eminent moral philosopher in the English-speaking world. The theory for which Hare was famous – prescriptivism, or ‘preference utilitarianism’, as it was called, the contention that one should act in such a way as to maximize people’s preferences – seemed to me to be obviously refuted as it made no provision for moral weakness, a fact which taught me how very silly very clever people could be.

After Balliol, Fr. Ker won a scholarship to study English at Corpus Christi, Oxford, where he was taught by another notable figure, the English don F. W. Bateson. In 1951, Bateson founded Essays in Criticism, which succeeded F. R. Leavis’s Scrutiny as the pre-eminent scholarly journal in its field after the latter folded in 1953. Advocating for what he called the ‘scholar-critic’, Bateson once wrote that ‘Dr Leavis at his best is a much better literary critic than I am but when it comes to scholarship, I am perhaps the better man of the two …’ In a witty piece on Bateson in Essays in Criticism, Valentine Cunningham quoted the don’s conclusion that ‘The scholar-critic must be a scholar, a researcher, before he can become a really competent critic. There are therefore almost no reputable scholar-critics’, to which Cunningham added: ‘And so it was with Freddy Bateson.’ Yet Bateson may have been surprised to know that in having Ian Ker as his student he had someone who would go on to become one of the most talented and accomplished scholar-critics that Oxford has ever produced. His work on Newman, Chesterton, and the authors of the Catholic Revival amply attest to this. Indeed, his essay on Evelyn Waugh is the single best thing ever written about the great Catholic novelist.

From Oxford, Fr. Ker went to Trinity College, Cambridge where he undertook doctoral work on George Eliot, which, however, the university rejected. Ian Jack, the crack editor of Emily Brontë and Robert Browning, was apparently not interested in hearing what Fr Ker had to say of George Eliot’s treatment of the Christian religion in her fiction. “If God is anywhere,” the agnostic Jack told his obituarist, “he is in the mind of man” – a sentiment which explains his otherwise unaccountable indifference. However, the honorary doctorates that Fr. Ker received subsequently from several universities in England and North America more than compensated for his unrewarded labors at Cambridge when he was a young man, though Cambridge did eventually award him a doctorate for his published work.

From Trinity College, Fr. Ker went to teach at the University of York, about which he recalled: “I got the job at York because it was a department of English and Related Literature and I was able to teach Latin as well as English literature. I was very lucky to get a job in one of the best English departments in the country and in such a historic and beautiful city at a time when academic jobs in the humanities were growing increasingly scarce.” Coincidentally enough, it was also at York that he encountered Leavis as a colleague, whom he found dour and unapproachable. At York, Fr. Ian liked to relate, the famously astringent critic was wary of other faculty, with whom he rarely spoke, though he could often be seen walking about the grounds picking up litter. A visitor noticing Leavis engaged thus remarked on the grounds’ extraordinary neatness, to which the vice chancellor replied that York had a very good grounds staff. It was also at York that Fr. Ker met John Roe, the noted Shakespeare scholar, with whom he remained friends for life.

That Fr. Ker came up with first-rate literary critics still on the scene (all progeny in one way or another of T. S. Eliot) accounts for something of his own critical rigor. Indeed, in later years, Fr. Ker often confided that he would have liked to have written a critical biography of Eliot – something the world still lacks.

Regarding his conversion when he was at Oxford, Fr. Ker remarked: “Although my father was a professed atheist, I think his dogmatic dismissal of Christianity provoked in me the opposite reaction and in my teens, I was greatly influenced by C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity (1952). Later his argument from Origen that either Christ was who he claimed to be or a scoundrel influenced my conversion to Catholicism as exactly the same argument seemed to me to apply to the pope.” Between writing his great biographies, Fr. Ker would write a brilliant response to Lewis with a work of apologetics of his own, Mere Catholicism (2007), which argued that mere Christianity, ineluctably, could not be other than mere Catholicism. Over the years, to Fr. Ker’s delight, this gem of a book has brought many converts into the Church from around the world, though later he would admit to me that he ought to have paid more attention to miracles in the book. Like Newman and, for that matter, Waugh, Fr. Ker was very alive to the operations of Providence and grace in the fallen world. After all, he was directly instrumental in the two miracles that canonized Newman.

Once Fr. Ker decided to convert, the reaction of his parents was mixed. “My father was indifferent to my becoming a Catholic, my mother wasn’t pleased – although she eventually became a Catholic herself. There were already several Catholics in the English Department at York. I always saw my teaching role, like Newman had seen his, as a pastoral as well as an educational role. One reason why I became a priest was because I thought I would like to teach people about Catholicism as opposed to English literature. My colleagues were amazed when they heard I was going to become a priest. Although I went to daily Mass I never advertised the fact, nor did I give the appearance of being pious.”

As for his decision to work on Newman, it was serendipitous in the way that Providential choices often are. “I knew a bit about Newman from reading Victorian literature and I had read the Apologia (1864) once when I was ill in bed – without I am afraid it making much of an impression on me. It was a chance encounter that got me writing about Newman: a colleague invited me to dinner in London where I met an Italian academic who was aiming to publish a selection of Newman’s works in Italian and who invited me to edit The Idea of a University (1873), which he later suggested I turn into an Oxford critical edition.” Fr. Ker’s friendship with the brilliant Newman scholar, Fr. Charles Stephen Dessain, would also inform his work on Newman – proof of the vitality of that personal influence of which Newman was always so appreciative. Moreover, Newman’s devotion to his sister, Mary, who died young, particularly appealed to Fr Ker, who was devoted to his sister, Susan, who also died young. He kept a photograph of Susan on his mantlepiece and dedicated his Newman biography to her.

After his conversion, Fr. Ker, as he recalled, was ‘offered an endowed chair not in English but in theology and philosophy at the University of St Thomas in St Paul, Minnesota on the basis of what I had published about Newman. even though I had no degree in theology, having studied privately for ordination (like Pope St Paul VI).’ St Thomas suited Fr. Ker. “I had been given to understand that mid-western Americans were dull characterless people but I certainly didn’t find that there: I lived in a residence for priests teaching at the university and I found myself in the company of some wonderful eccentrics. It was one of the happiest times in my life and I made many friends there, I returned to England because my parents were growing old and needed care (my only surviving sibling had long lived in Canada). I also regretted no longer doing pastoral work apart from supplies and hearing confessions at the local seminary.”

Fr. Ker’s fondness for the many students, scholars, priests and religious he has met over the years in North America, Europe and elsewhere points to another similarity he has with Newman, and that is his talent for friendship. Although not always adept at suffering fools as gladly as he might, especially fools given to distorting Newman or the Catholic Faith, Fr Ker always inspired fondness in those who reveled in his wit, his bonhomie, his learning, and his very real, if inconspicuous pietas.

Upon returning to England, Fr. Ker joined the theology faculty of Oxford and became parish priest of the Church of SS Thomas More and John Fisher at Burford in the Cotswolds, thus, ensuring that in his critical, biographical, theological and apologetical work he would always be grounded, as Newman had been grounded, in pastoral work. For both, in all they did, the cure of souls was paramount.

In the second half of the twentieth century, biography, especially literary biography, enjoyed something of a renaissance – one thinks of such gifted critical biographers as Peter Brown on Saint Augustine, Leon Edel on Henry James, Michael Holroyd on Bernard Shaw, Richard Holmes on Coleridge, Robert Baldick on J. K. Huysmans, E. P. Lock on Edmund Burke, and Walter Jackson Bate on Samuel Johnson. As a critical biographer, Fr. Ker very much belongs in this distinguished company. In his biography of Newman, he encapsulated his subject’s quest for reality by translating Newman’s epitaph, Ex umbria et imaginibus in veritatem: ‘Out of Unreality into Reality’. In his biography of Chesterton, Fr. Ker persuasively argued that GKC was Newman’s successor precisely because he shared the convert’s passion for reality, a quality which Hilaire Belloc also discerned in his friend. “Truth had for him,” Belloc recalled, “the immediate attraction of an appetite. He was hungry for reality. But what is much more, he could not conceive of himself except as satisfying that hunger […] it was not possible for him to hold anything worth holding that was not connected with the truth as a whole.” Here was the hunger that drove the Christian witness of both Newman and Chesterton, and Fr. Ker brilliantly recreates it in his magisterial biographies.

Another virtue of the Chesterton biography is its identifying and setting out the major themes that preoccupied GKC in his massive, though uneven oeuvre, including not only his well-known philosophy of wonder but the principle of limitation that governs his thinking about art, literature, history and religion and the role of the imagination in enabling us to see familiar matters anew. Distillation is one of the hallmarks of Fr. Ker’s work as a biographer, and it is particularly evident in his biography of Chesterton.

Fr. Ker’s biography of Newman, in all its amplitude and acuity, is a model life not only because of its critical rigor but its unusual precision. Newman lay great store by what he called ‘clearness’, which he found preeminently in Cicero. “I may truly say that I have never been in the practice since I was a boy of attempting to write well, or to form an elegant style,” Newman once confessed to a correspondent; “my one desire and aim has been to do what is so difficult – viz., to express clearly and exactly my meaning.” Fr. Ker follows Newman in this most demanding of all stylistic virtues. In his limpid prose, there is an unfailing fidelity to both the complexity and the simplicity of Newman’s work. He eschewed paraphrase. In all that he wrote of Newman, he was careful to present his subject in his own words.

Fr. Ker’s prose, moreover, is always attentive to Newman’s wit. As Anglican Difficulties (1850) and The Present Position of Catholics (1851) so richly attest, Newman was a satirist of the first order – his only peer is Swift – and one of the best things about Fr. Ker’s writings on Newman is how nicely they capture this satirical wit in all of its exquisite fun. In an essay on Newman that he contributed to The Oxford Handbook of English Literature and Theology (2009), for example, Fr. Ker remarks:

Newman’s first novel, Loss and Gain, which was also the first book he published as a Roman Catholic, opens his most creative period as a satirist. Running through the novel is a strong, often comic, sense of the real and the unreal. The issue for the hero Charles Reding becomes not so much which is the true religion, but which is the real religion. The doctrinal comprehensiveness of the Church of England is perceived not as a source of strength but as fatal to its reality, for two contradictory views cannot ‘both be real’. In the face of broad or liberal Anglicanism, it is no longer a question of satirizing inconsistencies, but of satirizing inconsistency itself as an ideal.

And then Fr. Ker proceeds to quote this brilliant effusion from the junior don, Mr. Vincent, who was “ever […] converting pompous nothings into oracles’ and ‘had a great idea of the via media being the truth’.

‘Our Church’, he said, ‘admitted of great liberty of thought within her pale. Even our greatest divines differed from each other in many respects; nay, Bishop Taylor differed from himself. It was a great principle in the English Church. Her true children agree to differ. In truth’, he continued, ‘there is that robust, masculine, noble independence in the English mind, which refuses to be tied down to artificial shapes, but is like, I will say, some great and beautiful production of nature—a tree, which is rich in foliage and fantastic in limb, no sickly denizen of the hothouse, or helpless dependent of the garden wall, but in careless magnificence sheds its fruits upon the free earth, for the bird of the air and the beast of the field, and all sorts of cattle, to eat thereof and rejoice.’

Since Fr. Ker brought out several works supplemental to his Newman biography, including essays on different aspects of the saint’s life and work, critical editions of the Idea of a University, the Apologia, and the Grammar of Assent, as well as monographs on his spiritual development, engagement with the full spectrum of Christianity, and what the great convert might have made of Vatican II in a book full of shrewd theological insights, he has given his readers an incomparably well-rounded portrait of Newman. All who delight in Newman owe him an inestimable debt.

Towards the end of his life, Fr Ker retired to Cheltenham Spa, where he was lovingly looked after by Mrs. JuliaKadziela, of whom he was immensely fond.

Once, when speaking with Fr. Ker over lunch in a charming little Italian restaurant in Cheltenham, I asked him which proof for the existence of God he found most persuasive, and, without hesitation, he replied, “the lives of the saints.” Since Fr. Ker spent much of his long, prolific, faithful life celebrating the gifts of sanctity, which only God bestows, there was an ungainsayable authority in his decided judgement. But even on that occasion, a touch of comedy, typical of any meeting with the great scholar, intervened. When we had finished our lunch and went outside to wait for a taxi, the restaurant’s proprietor, an elegant Italian gentleman accompanied us and while Fr. Ian was getting into the taxi, he turned to me and asked, “Who is this gentleman? He always comes to my restaurant with others from around the world who treat him with the greatest respect. Is he a famous man?” “Very famous,” I replied, “Fr. Ian Ker is the greatest biographer of England’s greatest saint.”

Source: www.catholicworldreport.com

About the Autor

Edward Short

Edward Short is the author of Newman and his Contemporaries, Newman and his Family, and Newman and History, as well as Adventures in the Book Pages: Essays and Reviews. He chose the poetry for The Saint Mary’s Book of Christian Verse (Gracewing, 2022), as well as an Introduction. He lives in New York with his wife and two young children.

Recent publication

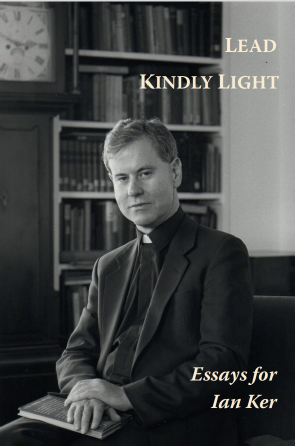

Lead Kindly Light:

Essays for Ian Ker

Lead Kindly Light: Essays for Ian Ker (Gracewing) is an excellent book for readers who would like to read more about Father Ker’s legacy.

Photo showing Ian Ker courtesy of Gracewing.